Author: Laura Beil / Source: Science News

On the hormonal roller coaster of life, the ups and downs of childbirth are the Tower of Power. For nine long months, a woman’s body and brain absorb a slow upwelling of hormones, notably progesterone and estrogen.

The ovaries and placenta produce these two chemicals in a gradual but relentless rise to support the developing fetus.With the birth of a baby, and the immediate expulsion of the placenta, hormone levels plummet. No other physiological change comes close to this kind of free fall in both speed and intensity. For most women, the brain and body make a smooth landing, but more than 1 in 10 women in the United States may have trouble coping with the sudden crash. Those new mothers are left feeling depressed, isolated or anxious at a time society expects them to be deliriously happy.

This has always been so. Mental struggles following childbirth have been recognized for as long as doctors have documented the experience of pregnancy. Hippocrates described a woman’s restlessness and insomnia after giving birth. In the 19th century, some doctors declared that mothers were suffering from “insanity of pregnancy” or “insanity of lactation.” Women were sent to mental hospitals.

Modern medicine recognizes psychiatric suffering in new mothers as an illness like any other, but the condition, known as postpartum depression, still bears stigma. Both depression and anxiety are thought to be woefully underdiagnosed in new mothers, given that many women are afraid to admit that a new baby is anything less than a bundle of joy. It’s not the feeling they expected when they were expecting.

Treatment — when offered — most commonly involves some combination of antidepression medication, hormone therapy, counseling and exercise. Still, a significant number of mothers find these options wanting. Untreated, postpartum depression can last for years, interfering with a mother’s ability to connect with and care for her baby.

Although postpartum depression entered official medical literature in the 1950s, decades have passed with few new options and little research.

Even as brain imaging has become a common tool for looking at the innermost workings of the mind, its use to study postpartum depression has been sparse. A 2017 review in Trends in Neurosciences found only 17 human brain imaging studies of postpartum depression completed through 2016. For comparison, more than four times as many have been conducted on a problem called “internet gaming disorder” — an unofficial diagnosis acknowledged only five years ago.

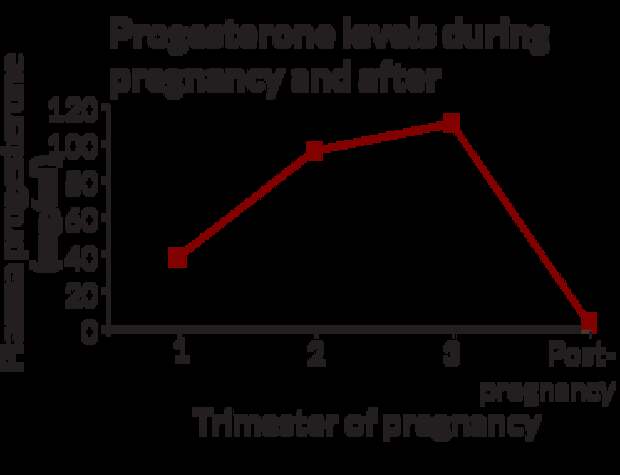

The hormone progesterone rises far above typical levels during pregnancy, then plummets after childbirth. Researchers are investigating how this and other changes contribute to postpartum depression.

Source: K.D. Pennell, M.A. Woodlin and P.B. Pennell/Steroids 2015

Now, however, more researchers are turning their attention to this long-neglected women’s health issue, peering into the brains of women to search for the root causes of the depression. At the same time, animal studies exploring the biochemistry of the postpartum brain are uncovering changes in neural circuitry and areas in need of repair.

And for the first time, researchers are testing an experimental drug designed specifically for postpartum depression. Early results have surprised even the scientists.

Women’s health experts hope that these recent developments signal a new era of research to help new moms who are hurting.

“I get this question all the time: Isn’t it just depression during the postpartum period? My answer is no,” says neuroscientist Benedetta Leuner of Ohio State University. “It’s occurring in the context of dramatic hormonal changes, and that has to be impacting the brain in a unique way. It occurs when you have an infant to care for. There’s no other time in a woman’s life when the stakes are quite as high.”

Even though progesterone and estrogen changes create hormonal whiplash, pregnancy wouldn’t be possible without them. Progesterone, largely coming from the ovaries, helps orchestrate a woman’s monthly menstrual cycle. The hormone’s primary job is to help thicken the lining of the uterus so it will warmly welcome a fertilized egg. In months when conception doesn’t happen, progesterone levels fall and the uterine lining disintegrates. If a woman becomes pregnant, the fertilized egg implants in the uterine wall and progesterone production is eventually taken over by the placenta, which acts like an extra endocrine organ.

Like progesterone, estrogen is a normal part of the menstrual cycle that kicks into overdrive after conception. In addition to its usual duties in the female body, estrogen helps encourage the growth of the uterus and fetal development, particularly the formation of the hormone-producing endocrine system.

These surges in estrogen and progesterone, along with other physiological changes, are meant to support the fetus. But the hormones, or chemicals made from them, cross into the mother’s brain, which must constantly adapt. When it doesn’t, signs of trouble can appear even before childbirth, although they are often missed. Despite the name “postpartum,” about half of women who become ill are silently distressed in the later months of pregnancy.

Decades ago, controversy churned over whether postpartum depression was a consequence of fluctuating hormones alone or something else, says neuroscientist Joseph Lonstein of Michigan State University in East Lansing. He studies the neurochemistry of maternal caregiving and postpartum anxiety. Lonstein says many early studies measured hormone levels in women’s blood and tried to determine whether natural fluctuations were associated with the risk of postpartum depression. Those studies found “no clear correlations with [women’s] hormones and their susceptibility to symptoms,” he says. “While the hormone changes are certainly thought to be involved, not all women are equally susceptible. The question then became, what is it about their brains that makes particular women more susceptible?”

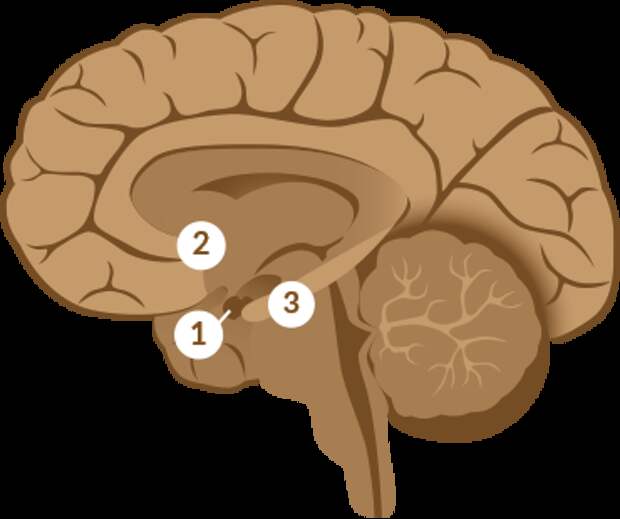

Research in rodents, along with imaging studies in new mothers, are finding areas of the brain that could be involved in postpartum depression. Among them:

1. Amygdalae Sometimes called the body’s “emotional thermostat,” these two structures are deep in the brain, one on each side. Studies suggest that, among other things, depressed mothers have heightened amygdala responses to an unfamiliar baby, perhaps blunting the response to their own child.

2. Nucleus accumbens Famous for its role in reward, pleasure and addiction, this area showed less ability to change in a study of rats with symptoms of postpartum depression.

3. Hippocampus This region contains receptors for neurosteroids, potent products of the hormone progesterone. During pregnancy, the number of neurosteroid receptors typically drops, presumably to protect the brain from high levels of progesterone and estrogen circulating at the same time. When progesterone drops immediately following loss of the placenta after birth, the receptors repopulate. But depressed women may not experience this rebound.

Seeking answers, researchers have examined rodent brains and placed women into brain scanners to measure the women’s responses to pictures or videos of babies smiling, babbling or crying. Though hormones likely underlie the condition, many investigations have led to the…

The post Depression among new mothers is finally getting some attention appeared first on FeedBox.