Author: Cara Giaimo / Source: Atlas Obscura

On August 31st, 1818, around 3 p.m., the Arctic explorer John Ross was called away from his dinner and onto the deck of the ship he commanded, the Isabella. Ross and his crew were moored in Baffin Bay, just south of Greenland, seeking a way through to the Arctic sea beyond.

All day, they had been waiting for the fog to clear, so they could take a look around and try to find it.Ross stepped out onto the deck and began scanning the horizon: ice, more ice, and, in between, an imposing set of peaks. “I distinctly saw the land, round the bottom of the bay, forming a connected chain of mountains with those which extended along the north and south sides,” he wrote soon after. There was, he concluded, no way through.

Some are born great; some achieve greatness; some have greatness thrust upon them. And some narrowly miss greatness, kept from it by a pesky propensity to imagine land where there is none. Such is the case of Ross, who was just one fake mountain range away from discovering a critical entrance to the Northwest Passage, and more lasting explorational fame. No one is sure why he saw them—but, in the words of one biographer, the false mountains “would haunt Ross for the rest of his life.”

According to a biography by M.J. Ross, John started sailing professionally in 1786, when he was just nine years old, and was on the water “almost continuously” after that. In December of 1817, the British Admiralty decided to send a couple of ships up to the Arctic, “to ascertain the existence or non-existence of a north-west passage,” as Ross later put it to a friend. The expedition was in need of a commander—was Ross up to the task? He accepted, and by April of the following year, he had chosen his ships—the formidable Isabella and the smaller Alexander—gathered his crew, loaded up with thousands of pounds of beef, bread, and raisins, and set a course for the North.

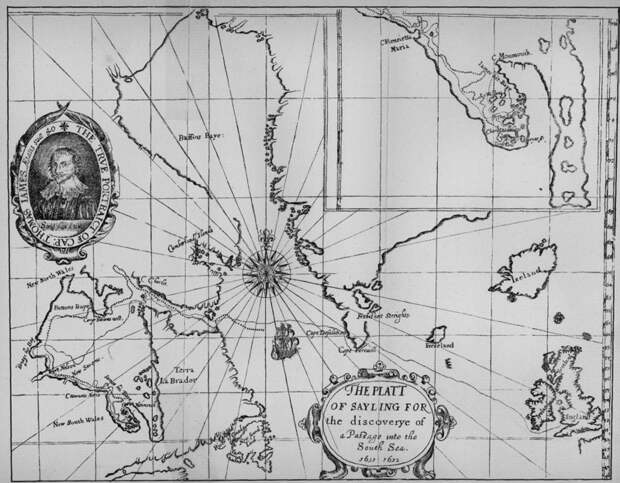

The British had been actively looking for the Northwest Passage since the end of the 15th century, when King Henry VII sent the explorer John Cabot to find a more direct route to China. (From 1744 to 1818—the year Ross set out—there was even prize money at stake.) Although certain expeditions had managed to push deeper into the massive archipelago north of the Canadian mainland, no one had yet found a way through.

For this new expedition, Ross was told to follow a forceful northward current, which had previously been reported by whalers. That current shot through the water south of Greenland and continued up along the coast of Canada. Its strength suggested it came from the open ocean, and that following it would lead there. “Having rounded the northeastern point of the North American continent,” wrote M.J. Ross, “he was to steer straight for Bering Strait, enter the Pacific, hand over a copy of his journals to the Russian governor of Kamchatka for dispatch to London, and proceed to Hawaii for replenishment and recreation—an enticing prospect!”

This indeed sounded nice. But once the explorers got to the icier parts of the ocean, the reality was a bit more of a slog. In early June, Ross wrote, the Isabella and the Alexander found themselves trapped in a semi-frozen strait, trapped by “at least seven hundred icebergs” alongside a few dozen whaling ships. (Ross amused himself by pulling up specimens of starfish, mud, and worms from the ocean floor, using a scientific instrument of his own devising, which he called the “Deep Sea Clamm.”)

For much of late July,…

The post How A Fake Mountain Range Slowed Down Arctic Exploration appeared first on FeedBox.