Author: Paula Mejia / Source: Atlas Obscura

In late January, a no-frills Irish pub in Chicago, the Brehon, invited a small selection of guests for a night of light appetizers and drinks. The gathering wasn’t a supper club, or a private party. The event commemorated the 40th anniversary of the bar’s previous iteration, the Mirage Tavern, and the paradigm-shifting investigation that took place within it.

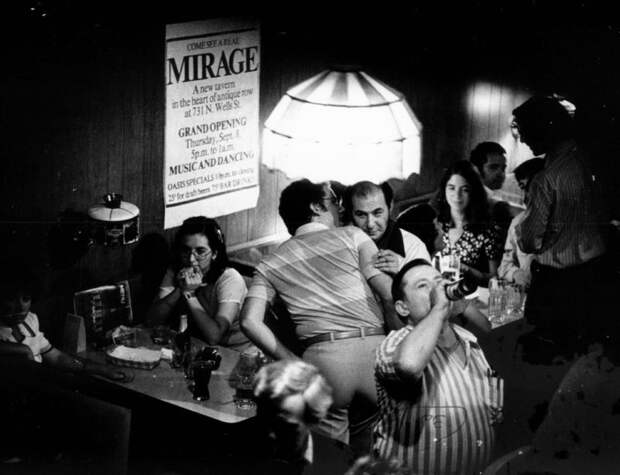

While the Mirage had the appearance of (and all the fixings of) a good ’70s dive bar, including dirt-cheap drinks and games, it was actually a front. In 1977, a group of journalists from the Chicago Sun-Times bought the derelict watering hole and operated it in secret for several months. The Mirage turned into one of the most contentious, precedent-setting experiments in investigative journalism to date, which, in turn, revealed an intricate web of corruption, bribery, negligence, and tax evasion.

It’s well-known that Chicago has a long history as a hotbed of organized crime and political corruption. But players and civilians alike aren’t often willing to talk to journalists about the nitty-gritty of how this happens. At least, not on the record. That’s why Upton Sinclair went incognito in order to reveal the horrid conditions of Chicago’s meatpacking plants at the turn of the century. It’s also what led Pam Zekman to convince the Chicago Sun-Times that they should buy a dive bar in the name of investigative journalism.

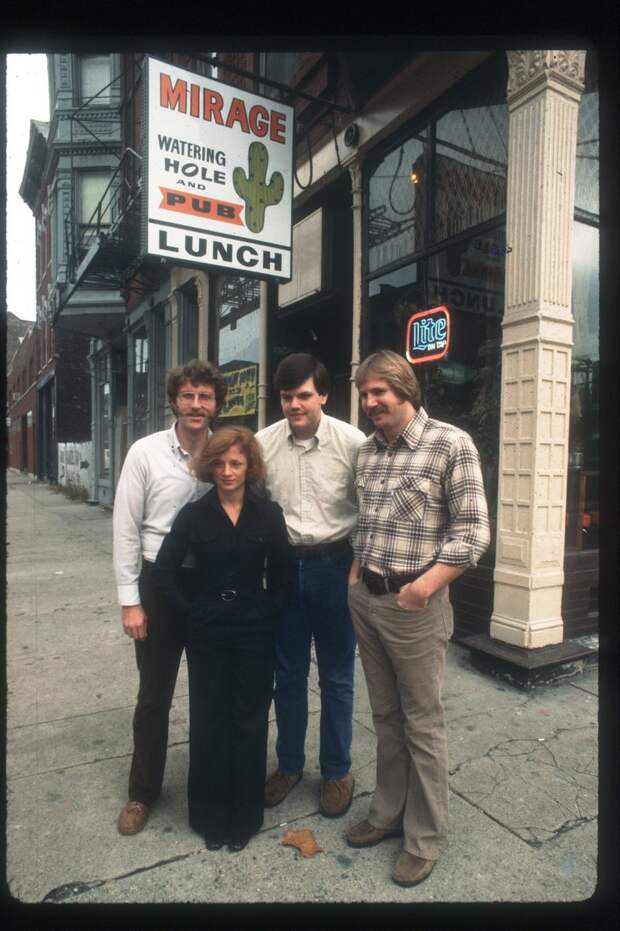

Before coming on as a reporter for Sun-Times, Zekman had been part of a team at the Chicago Tribune that brought a series of abuses, including medical malpractice, to light by going undercover at hospitals and nursing homes. By the mid-1970s, Zekman had become entrenched in reporting on Chicago’s underground network of corruption and bribery. Frustrated that no one would talk to her for a story, though, she took a cue from her past undercover work and, along with her mentor George Bliss, Zekman proposed that a team of reporters should pose as the owners and operators of a bar in the city’s River North neighborhood.

The Tribune declined, but the Sun-Times was up for it. So they partnered with the Better Government Association, a watchdog group that looked into local corruption, and bought themselves a watering hole. Why a bar, though? “We started getting phone calls from businesses that were complaining about having to pay a steady stream of inspectors that come into the restaurants and bars looking for payoffs to ignore city violations,” Zekman said in an oral history.

The group settled on a tavern known as the Firehouse, located on the corner of North Wells and Superior, due to how close it was to the paper’s offices. They renamed it the Mirage. There wasn’t anything illustrious about the place. As one of the reporters, Zay N. Smith, remembers: “It was dirty, badly kept, just kind of a hang-out for a few tipplers in the neighborhood.” Zekman and Bill Recktenwald (of the BGA) posed as the married owners of said bar, “Pam and Ray Patterson.” People were more than willing to talk to them now—starting with the business broker who, upon helping the two buy the the joint, told them right out the gate that he’d lend them a hand paying off building and fire inspectors with cash, and…

The post How a Chicago Dive Bar Exposed Corruption and Changed Journalism appeared first on FeedBox.