Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“Every formula which expresses a law of nature is a hymn of praise to God,” pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell wrote as she contemplated science, spirituality, and our conquest of truth. A century later, Carl Sagan tussled with the same question shortly before his death: “The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both. ”

It is, of course, an abiding question, as old as consciousness — we are material creatures that live in a material universe, yet we are capable of experiences that transcend what we can atomize into physical facts: love, joy, the full-being gladness of a Beethoven symphony on a midsummer’s night.

The Nobel-winning physicist Niels Bohr articulated the basic paradox of living with and within such a duality: “The fact that religions through the ages have spoken in images, parables, and paradoxes means simply that there are no other ways of grasping the reality to which they refer. But that does not mean that it is not a genuine reality. And splitting this reality into an objective and a subjective side won’t get us very far.”

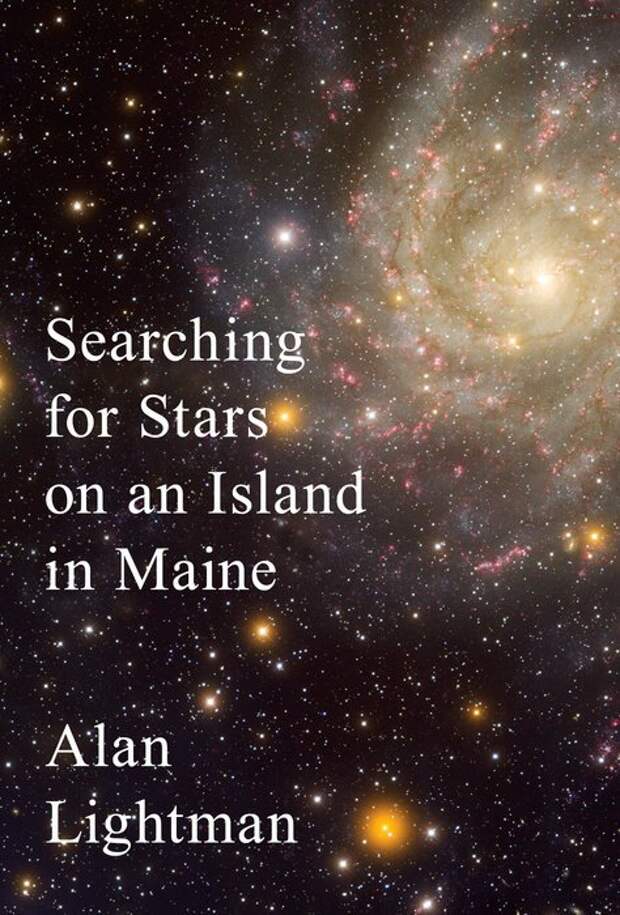

Nearly a century after Bohr, the physicist and writer Alan Lightman takes us further, beyond these limiting dichotomies, in Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine (public library) — a lyrical and illuminating inquiry into our dual impulse for belief in the unprovable and for trust in truth affirmed by physical evidence. Through the lens of his personal experience as a working scientist and a human being with uncommon receptivity to the poetic dimensions of life, Lightman traces our longing for absolutes in a relative world from Galileo to Van Gogh, from Descartes to Dickinson, emerging with that rare miracle of insight at the meeting point of the lucid and the luminous.

Lightman, who has previously written beautifully about his transcendent experience facing a young osprey, relays a parallel experience he had one summer night on an island off the coast of Maine, where he and his wife have been going for a quarter century. On this small, remote speck of land, severed from the mainland without ferries or bridges, each of the six families has had to learn to cross the ocean by small boat — a task particularly challenging at night. Lightman recounts the unbidden revelation of one such nocturnal crossing:

No one was out on the water but me. It was a moonless night, and quiet. The only sound I could hear was the soft churning of the engine of my boat. Far from the distracting lights of the mainland, the sky vibrated with stars. Taking a chance, I turned off my running lights, and it got even darker. Then I turned off my engine. I lay down in the boat and looked up. A very dark night sky seen from the ocean is a mystical experience. After a few minutes, my world had dissolved into that star-littered sky. The boat disappeared. My body disappeared. And I found myself falling into infinity. A feeling came over me I’d not experienced before… I felt an overwhelming connection to the stars, as if I were part of them. And the vast expanse of time — extending from the far distant past long before I was born and then into the far distant future long after I will die — seemed compressed to a dot. I felt connected not only to the stars but to all of nature, and to the entire cosmos. I felt a merging with something far larger than myself, a grand and eternal unity, a hint of something absolute. After a time, I sat up and started the engine again. I had no idea how long I’d been lying there looking up.

Lightman — the first professor at MIT to receive a dual faculty appointment in science and the humanities — syncopates this numinous experience with the reality of his lifelong devotion to science:

I have worked as a physicist for many years, and I have always held a purely scientific view of the world. By that, I mean that the universe is made of material and nothing more, that the universe is governed exclusively by a small number of fundamental forces and laws, and that all composite things in the world, including humans and stars, eventually disintegrate and return to their component parts. Even at the age of twelve or thirteen, I was impressed by the logic and materiality of the world. I built my own laboratory and stocked it with test tubes and petri dishes, Bunsen burners, resistors and capacitors, coils of electrical wire. Among other projects, I began making pendulums by tying a fishing weight to the end of a string. I’d read in Popular Science or some similar magazine that the time for a pendulum to make a complete swing was proportional to the square root of the length of the string. With the help of a stopwatch and ruler, I verified this wonderful law. Logic and pattern. Cause and effect. As far as I could tell, everything was subject to numerical analysis and quantitative test. I saw no reason to believe in God, or in any other unprovable hypotheses.

Yet after my experience in that boat many years later… I understood the powerful allure of the Absolutes — ethereal things that are all-encompassing, unchangeable, eternal, sacred. At the same time, and perhaps paradoxically, I remained a scientist. I remained committed to the material world.

Against our human finitude, temporality, and imperfection, these “Absolutes” offer infinity, eternity, perfection. Lightman defines them as concepts and beliefs that “refer to an enduring and fixed reference point that can anchor and guide us through our temporary lives” — notions like constancy, immortality, permanence, the soul, “God.”

Building on his earlier reflections on why we long for permanence in a universe of constant change, he writes:

A fascinating feature of the Absolutes — in fact, a defining feature — is that there is no way to get there from here, that is, from within the physical world. There is no gradual, step-by-step path to go from relative truth to absolute truth, or to go from a long period of time to eternity, or from limited wisdom to the infinite wisdom of God. The infinite is not merely a lot more of the finite. Indeed, the unattainability of the Absolutes may be part of their allure.

The final defining feature of these Absolutes, Lightman notes, is their unprovability by the scientific method. He writes:

Yet I did not need any proof of what I felt during that summer night in Maine looking up at the sky. It was a purely personal experience, and its validity and power resided in the experience itself. Science knows what it knows from experiment with the external world. Belief in the Absolutes comes from internal experience, or sometimes from received teachings and culture-granted authority.

Conversely, however, notions that belong to this realm of Absolutes fall apart when they make claims in the realm of science — claims disproven by the facts of the material world. With an eye to how the discoveries of modern science — from heliocentricity to evolution to the chemical composition of the universe — have challenged many of these Absolutes, Lightman writes:

Nothing in the physical world seems to be constant or permanent. Stars burn out. Atoms disintegrate. Species evolve. Motion is relative. Even other universes might exist, many without life. Unity has given way to multiplicity. I say that the Absolutes have been challenged rather than disproved, because the notions of the Absolutes cannot be disproved any more than they can be proved. The Absolutes are ideals, entities, beliefs in things that lie beyond the physical world. Some may be true and some false, but the truth or falsity cannot be proven.

Generations after Henry Miller insisted that “it is almost banal to say so yet it needs to be stressed continually: all is creation, all is change, all is flux, all is metamorphosis,” Lightman adds:

From all the physical and sociological evidence, the world appears to run not on absolutes but on relatives, context, change, impermanence, and multiplicity. Nothing is fixed. All is in flux.

[…]

On the one hand, such an onslaught of discovery presents a cause for celebration… Is it not a testament to our minds that we little human beings with our limited sensory apparatus and brief lifespans, stuck on our one planet in space, have been able to uncover so much of the workings of nature? On the other hand, we have found no physical evidence for the Absolutes. And just the opposite. All of the new findings suggest that we live in a world of multiplicities, relativities, change, and impermanence. In the physical realm, nothing persists. Nothing lasts. Nothing is indivisible. Even the subatomic particles found in the twentieth century are now thought to be made of even smaller “strings” of energy, in a continuing regression of subatomic Russian dolls. Nothing is a whole. Nothing is indestructible. Nothing is still. If the physical world were a novel, with the business of examining evil and good, it would not have the clear lines of Dickens but the shadowy ambiguities of Dostoevsky.

Indeed, Dostoevsky himself may be the prophet laureate of Absolutes, for he asserted a lifetime ahead of Lightman that

The post Alan Lightman on the Longing for Absolutes in a Relative World and What Gives Lasting Meaning to Our Lives appeared first on FeedBox.