Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

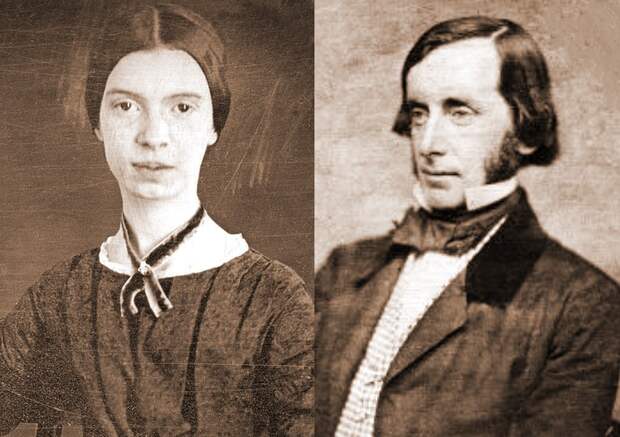

“You can never be sure / you die without knowing / whether anything you wrote was any good / if you have to be sure don’t write,” W.S. Merwin wrote in his gorgeous poem encapsulating his greatest mentor’s advice. No one has embodied this ethos more fully than Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830–May 15, 1886), who lived and died a century earlier never knowing whether anything she wrote was any good, never knowing whether and how and that her body of work would revolutionize literature and rewrite the common record of human thought and feeling.

In her thirty-first year, on the pages of a national magazine, Dickinson — a central figure in Figuring, from which this essay is adapted — encountered the person who would become the closest thing she ever had to a literary mentor.

In the spring of 1862, exactly four decades ahead of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, The Atlantic Monthly published a twenty-page piece titled “A Letter to a Young Contributor” by the abolitionist and women’s rights advocate

Addressing young writers — primarily the many women who sent the Atlantic manuscripts for consideration under male pseudonyms — the thirty-nine-year-old Higginson writes:

No editor can ever afford the rejection of a good thing, and no author the publication of a bad one. The only difficulty lies in drawing the line.

A good editor, Higginson asserts, has learned to draw that line by having “educated his eye till it has become microscopic, like a naturalist’s, and can classify nine out of ten specimens by one glance at a scale or a feather.” He chooses a strangely morbid metaphor to illustrate the editorial challenge and thrill of finding that rare undiscovered genius among “the vast range of mediocrity”:

To take the lead in bringing forward a new genius is as fascinating a privilege as that of the physician who boasted to Sir Henry Halford of having been the first man to discover the Asiatic cholera and to communicate it to the public.

He goes on to offer a bundle of advice on how an aspiring writer is to court her prospective editor: Revise amply before sending in your manuscript; write legibly with “good pens, black ink, nice white paper and plenty of it”; develop a style of expression not “polite and prosaic” but “so saturated with warm life and delicious association that every sentence shall palpitate and thrill with the mere fascination of the syllables”; counterbalance profundity of sentiment with levity of style; know that “there is no severer test of literary training than in the power to prune out your most cherished sentence, when you find that the sacrifice will help the symmetry or vigor of the whole”; don’t show off your erudition but showcase its fruits; and remember that “a phrase may outweigh a library.” He writes:

There may be phrases which shall be palaces to dwell in, treasure-houses to explore; a single word may be a window from which one may perceive all the kingdoms of the earth and the glory of them. Oftentimes a word shall speak what accumulated volumes have labored in vain to utter: there may be years of crowded passion in a word, and half a life in a sentence… Labor, therefore, not in thought alone, but in utterance; clothe and reclothe your grand conception twenty times, if need be, until you find some phrase that with its grandeur shall be lucid also.

In a sun-filled bedroom fifty miles to the west, a woman who had crowded lifetimes of passion into her thirty-one years and corked it up in the volcanic bosom of her being devoured the piece—a woman who would boldly defy Higginson’s indictment that a writer should use dashes only in…

The post Advice on Writing from Emily Dickinson’s Editor appeared first on FeedBox.