Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

With Carl Sagan’s poetic Pale Blue Dot on my mind lately, I have found myself dwelling on the color blue and the way our planet’s elemental hue, the most symphonic of the colors, recurs throughout our literature as something larger than a mere chromatic phenomenon — a symbol, a state of being, a foothold to the most lyrical and transcendent heights of the imagination.

Gathered here is a posy of blue from some of my favorite encounters with this more-than-color in the literature of the past two centuries.

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE (1810)

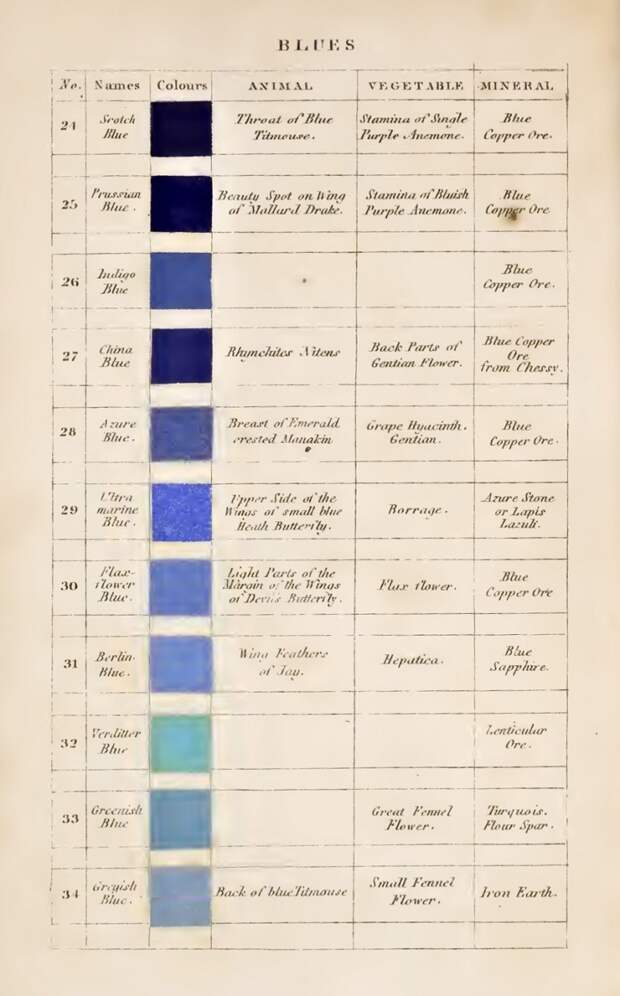

In his sixty-first year, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (August 28, 1749–March 22, 1832), by then Europe’s reigning intellect, published Theory of Colors (public library | public domain) — his effort to unearth the psychological link between color and emotion nearly a century before the dawn of psychology as a formal field of study, penned just before his compatriot Abraham Gottlob Werner released his seminal scientific nomenclature of color, which Darwin would later take on The Beagle.

“We love to contemplate blue,” Goethe wrote, “not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it.” The treatise, composed as a refutation of Newton, turned out to have no scientific validity. But its conceptual aspects fascinated and inspired generations of philosophers and scientists ranging from Arthur Schopenhauer to Kurt Gödel.

Goethe writes in the section allotted to blue:

As yellow is always accompanied with light, so it may be said that blue still brings a principle of darkness with it.

This color has a peculiar and almost indescribable effect on the eye. As a hue it is powerful — but it is on the negative side, and in its highest purity is, as it were, a stimulating negation. Its appearance, then, is a kind of contradiction between excitement and repose.

As the upper sky and distant mountains appear blue, so a blue surface seems to retire from us.

But as we readily follow an agreeable object that flies from us, so we love to contemplate blue — not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it.

Blue gives us an impression of cold, and thus, again, reminds us of shade… Rooms which are hung with pure blue, appear in some degree larger, but at the same time empty and cold.

The appearance of objects seen through a blue glass is gloomy and melancholy.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU (1843)

“Where is my cyanometer,” Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817–May 6, 1862) exclaimed in his splendid journal on a blue-skied spring day, referring to the curious device invented by the Swiss scientist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure a century earlier to measure the blueness of the sky, which the polymathic naturalist Alexander von Humboldt enthusiastically embraced. “We love to see any part of the earth tinged with blue, cerulean, the color of the sky, the celestial color,” Thoreau wrote in another spring entry. “The blue of my eye sympathizes with this blue in the snow,” he recorded in a winter one. “Blue is light seen through a veil,” he wrote on the precipice of the two seasons.

Thoreau’s writings, dancing at the borderline between observation and contemplation, are strewn with his love of blue. Most often, he records his delight at the raw reality of the color as he encounters it in nature. Occasionally, however, he leaps from the actual into the abstract, drawing from physical blueness insight into the metaphysical dimensions of existence.

In a travelogue from an 1843 walk to Waschusett, found in his indispensable Excursions (free ebook | public library) — the source of his lovely meditation on finding spiritual warmth in winter — Thoreau writes:

We resolved to scale the blue wall which bound the western horizon… In the spaces of thought are the reaches of land and water, where men go and come. The landscape lies far and fair within, and the deepest thinker is the farthest travelled.

Peering into the blue horizon from the conquered mountain summit at the end of the journey, he finds in it a metaphor for the boundlessness of the human spirit:

We will remember within what walls we lie, and understand that this level life too has its summit, and why from the mountain-top the deepest valleys have a tinge of blue; that there is elevation in every hour, as no part of the earth is so low that the heavens may not be seen from, and we have only to stand on the summit of our hour to command an uninterrupted horizon.

WASSILY KANDINSKY (1910)

Exactly a century after Goethe, the great Russian painter and art theorist Wassily Kandinsky (December 16, 1866–December 13, 1944) examined the psychological and spiritual dimensions of art through the lens of form and color. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art (free ebook | public library), Kandinsky devotes an especially impassioned section to blue:

The power of profound meaning is found in blue, and first in its physical movements (1) of retreat from the spectator, (2) of turning in upon its own centre. The inclination of blue to depth is so strong that its inner appeal is stronger when its shade is deeper. Blue is the typical heavenly colour… The ultimate feeling it creates is one of rest… [Footnote:] Supernatural rest, not the earthly contentment of green. The way to the supernatural lies through the natural.

When it sinks almost to black, it echoes a grief that is hardly human… When it rises towards white, a movement little suited to it, its appeal to men grows weaker and more distant. In music a light blue is like a flute, a darker blue a cello; a still darker a thunderous double bass; and the darkest blue of all — an organ.

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE (1916)

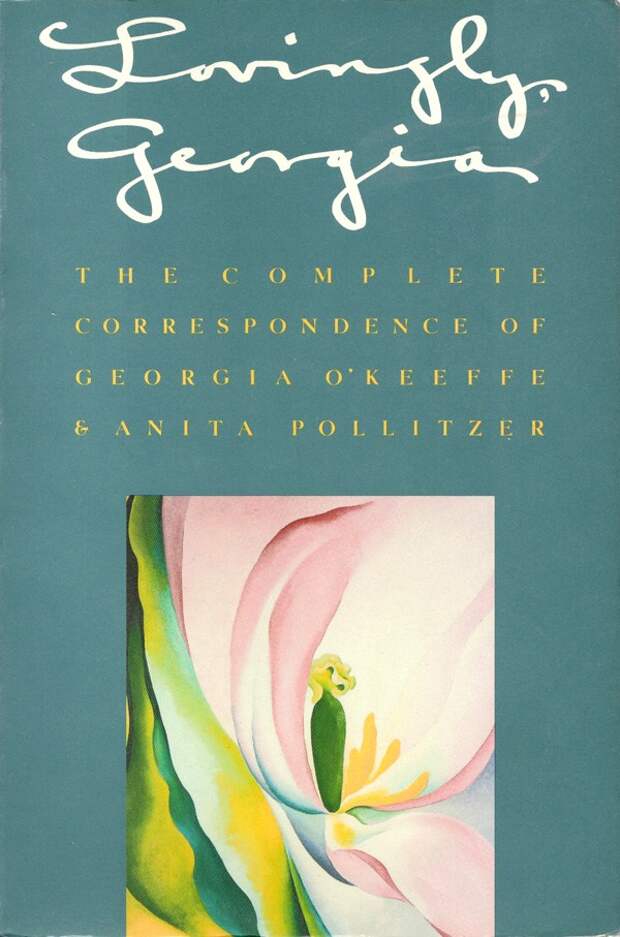

When Georgia O’Keeffe (November 15, 1887–March 6, 1986) was a little girl, decades before she came to be regarded as America’s first great female artist and became the first woman honored with a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, her mother used to read history and travel stories to her every night before bed. The mesmerism of place never lost its grip on her. At the peak of her career, O’Keeffe left New York and moved to the exotic expanse of the Southwest to live a solitary life. She once wrote in a letter to her dearest friend, Anita Pollitzer, who had selflessly taken it upon herself to make the New York art elite pay attention to O’Keeffe’s work: “I believe one can have as many rare experiences at the tail end of the earth as in civilization if one grabs at them — no — it isn’t a case of grabbing — it is — just that they are here — you can’t help getting them.” Pollitzer would later come to write in a major profile of O’Keeffe: “Fame still does not seem to be as meaningful or real to her as the mesas of New Mexico or the petals of a white rose.”

Or the blue of the Southwest sky, for what most enchanted O’Keeffe in her new home was the vast firmament with its tempest of color, richer than anything she had ever seen or even imagined possible. In a letter from September of 1916, found in Lovingly, Georgia: The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O’Keeffe and Anita Pollitzer (public library), O’Keeffe exults in the azure awe of the Southwest sky:

Tonight I walked into the sunset — to mail some letters — the whole sky — and there is so much of it out here — was just blazing — and grey blue clouds were riding all through the holiness of it — and the ugly little buildings and windmills looked great against it…

The Eastern sky was all grey blue — bunches of clouds — different kinds of clouds — sticking around everywhere and the whole thing — lit up — first in one place — then in another with flashes of lightning — sometimes just sheet lightning — and some times sheet lightning with a sharp bright zigzag flashing across it –. I walked out past the last house — past the last locust tree — and sat on the fence for a long time — looking — just looking at — the lightning — you see there was nothing but sky and flat prairie land — land that seems more like the ocean than anything else I know — There was a wonderful moon.

Well I just sat there and had a great time all by myself — Not even many night noises — just the wind —

[…]

It is absurd the way I love this country… I am loving the plains more than ever it seems — and the SKY — Anita you have never seen SKY — it is wonderful —

MARGARET MEAD (1926)

Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901–November 15, 1978), the color blue appeared not in the attentive observation of the real world that made her one of the most visionary and influential anthropologists in history, but in a nocturnal visitation of her own unconscious mind — a strange and wondrous dream about the meaning of life.

In a 1926 letter found in To Cherish the Life of the World: Selected Letters of Margaret Mead (public library) — which gave us Mead’s exquisite love letters to her lifelong soulmate and her advice on how to raise a child in an uncertain world — Mead recounts her nocturnal revelation:

Last night I had the strangest dream. I was in a laboratory with Dr. Boas and he was talking to me and a group of other people about religion, insisting that life must have a meaning, that man couldn’t live without that. Then he made a mass of jelly-like stuff of the most beautiful blue I had ever seen — and he seemed to be asking us all what to do with it. I remember thinking it was very beautiful but wondering helplessly what it was for. People came and went making absurd suggestions. Somehow Dr. Boas tried to carry them out — but always the people went away angry, or disappointed — and finally after we’d been up all night they had all disappeared and there were just the two of us. He looked at me and said, appealingly “Touch it.” I took some of the astonishingly blue beauty in my hand, and felt with a great thrill that it was living matter. I said “Why it’s life — and that’s enough” — and he looked so pleased that I had found the answer — and said yes “It’s life and that is wonder enough.”

VIRGINIA WOOLF (1937)

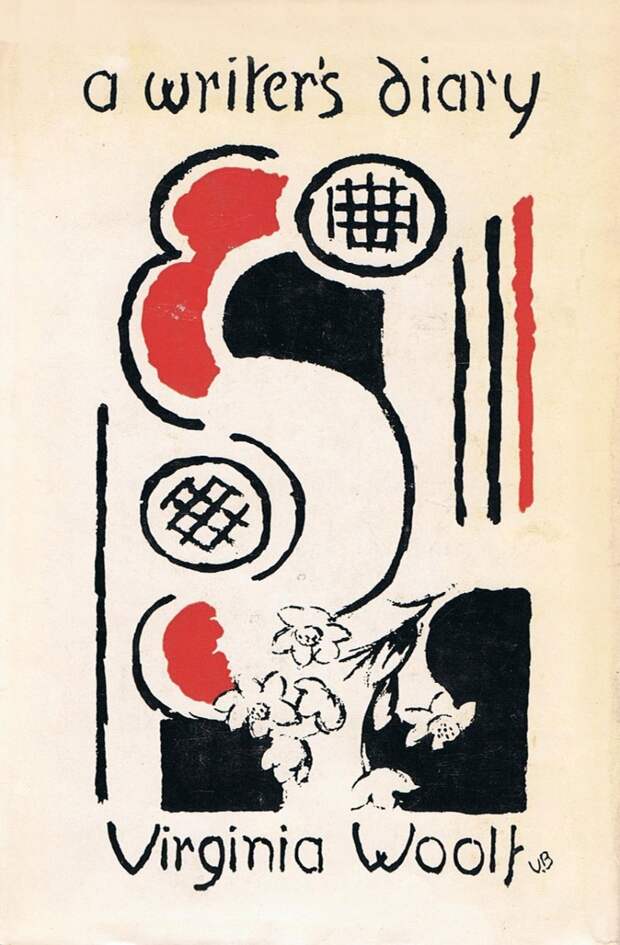

There is a strange paucity of blue in the private writings of literature’s bluest soul. Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941) rarely mentions the color throughout her journals, collected in A Writer’s Diary (public library) — the indispensable posthumous volume that gave us Woolf on the creative benefits of keeping a diary, the consolations of growing older, the relationship between loneliness and creativity, what makes love last, and her arresting account of a total solar eclipse.

But when she does turn to blue, it becomes more than a color, more than a mood — a subtle yet piercing hue of being, or rather the color of the lacuna between being and nonbeing. In an entry from April 9 of 1937, four springs before the blue of her lifelong depression and the River Ouse swallowed her, Woolf limns the singular blue of a particular interior space. Alluding to Wordsworth’s verse addressing “the heart that lives alone, housed in a dream,” she quotes another line and argues with the poet:

“Such happiness wherever it is known is to be pitied for tis surely blind.” Yes, but my happiness isn’t blind. That is the achievement, I was thinking between 3 and 4 this morning, of my 55 years. I lay awake so calm, so content, as if I’d stepped off the whirling world into a deep blue quiet space and there…

The post Two Hundred Years of Blue appeared first on FeedBox.