Author: Susan Milius / Source: Science News for Students

Today’s beef comes from animals raised on farms. So does chicken and pork. Fish? It comes from animals that live in water. But some scientists are looking to change that.

They’d like to grow just the parts we want to eat. Create burgers, for instance, without any cows. Make just the chicken nuggets and forget the rest of the chicken. Opinions differ on how best to do this. Some would start with animal cells. Others would reach for parts of plants instead. But whatever their source, the goals are the same: tasty meat for more people, less stress on the environment.

The idea of growing just the beef, not the whole cow, has been around since at least the 1890s. That sci-fi fantasy got a bit more real in 2013. That’s when Mark Post introduced his lab-grown hamburger at a televised tasting. He crafted it from what he called “cultured beef.” But the cost for that first burger was high — more than $300,000. No one expected anyone to buy a burger that cost more than a car, let alone a small plane. The idea was to show that it should be possible to grow real cow cells in a lab, without a farm or even a whole cow.

Other scientists want to make “meat” from plants. These dreamers are not looking to create a better “veggie burger.” Indeed, one of these scientists, Patrick O. Brown, doesn’t like that term at all. Veggie burgers are made from plants and have the shape of a burger. The taste is often quite different from true meat. Brown’s company, Impossible Foods in Redwood City, Calif., instead wants to make plant burgers so delicious that die-hard meat eaters will sigh happily and take another bite.

Brown’s goal: Identify those proteins or other molecules that give meats their texture and pleasing flavor. Then, track down each vital component from some nonanimal source.

When it comes to making meat, “Animals happened to be the technology that was available 10,000 years ago,” Brown says. “We stuck with that same technology. And it’s incredibly inefficient by any measure.”

Brown is convinced that science can come up with something better. His team is going the plant path. But if the “cultured” meat scientists can make their animal-cell-based dream affordable, he adds, “I’ll be their biggest fan.”

Why the push for a different ‘meat’

Many people like meat just the way it is. Yet they may not always grasp the role technology could play, says Bruce Friedrich. He’s executive director of the Good Food Institute. Based in Washington, D.C., it urges people to invent new ways of making meat.

People who love meat may not love how modern agriculture produces much of that meat, Friedrich says. Big industry can crowd animals in tight spaces. The animal’s wastes can harm the environment. And it takes loads of energy to feed, rear and slaughter livestock for meat. Change, he argues, is needed.

To be accepted, farm-free meats will have to be affordable. Maybe more importantly, they also will have to deliver on flavor. That’s no small challenge.

Hannah Laird is studying what people want their ground beef to taste like. At Texas A&M University in College Station, this meat scientist runs a sensory evaluation lab. Laird recruits beef lovers to spend six months to a year learning to pick out and score some 40 flavors and aromas that can show up in ground beef. Then for two hours at a time, her panelists sniff, taste and rate samples of beef. They score each of the flavors and aromas by comparing it to something else. For example, testers might give a mouthful of ground beef’s slight “metallic” taste a score of 6. That means it’s about as strong as the metal-like tang in Dole canned pineapples.

Raw beef is bland, Laird says. It mainly provides an aroma and flavor known as “bloody/serumy.” But cook that meat, and a whole new range of scents and flavors develop. Brown/roasted. Fatlike. Umami. Maybe smoky-charcoal — or, perhaps, smoky-wood. Or perhaps cocoa, salty, buttery, cumin or more floral flavors emerge. And for a less-than-perfect patty, testers might report “barnyard” (no surprise what that refers to).

Ground beef is so well known in America that one flavor is simply called “beef identity.”

Laird is finishing a project probing this intense culinary romance. “People say they want low-fat ground beef,” she says. In taste tests, however, when they don’t know the fat content of the meat, they’ll choose a 20-percent-fat burger over one with 10 percent fat almost every time. It all comes down to taste.

Taste preferences start forming in the womb, says Gary Beauchamp. He works at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, Pa. Tests there have detected how the food that a mom eats during pregnancy can influence what her baby will like to eat on its own.

But preferences can change. People who switch to low-salt diets are often miserable at first. Months later, Beauchamp says, these diners rate the taste of their once-beloved foods as too salty. It would be daunting to predict what might happen with meat preferences, he says.

An environmental case for synthetic meat

Getting diners to reach for farm-free meat may take some doing. But scientists see a range of reasons on why it’s worth getting them to try.

“Meat production is one of the most important ways in which humanity affects the environment,” wrote biologist Charles Godfray and his colleagues at England’s University of Oxford in the July 20 Science. For instance, they point out, raising livestock leaves big environmental hoofprints.

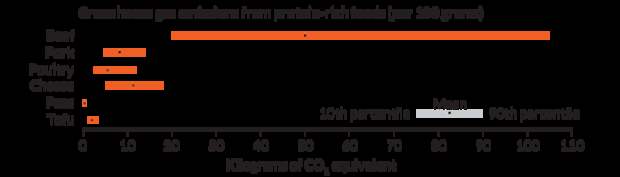

Greenhouse gases from animal farming account for more than one-seventh of all of those gases emitted by human activities. That estimate comes from a 2013 report by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

The post Designing tomorrow’s burger appeared first on FeedBox.