Author: Jim Baggott / Source: Big Think

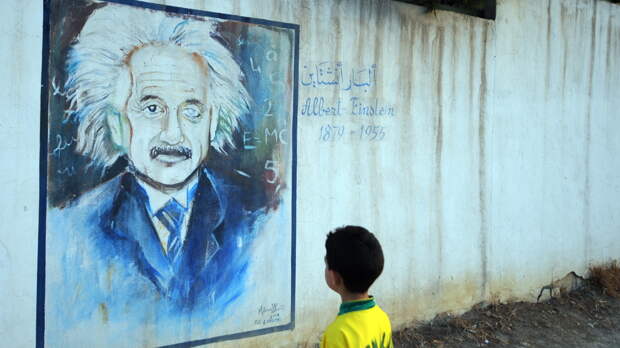

‘The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’

Einstein was responding to a letter from the German physicist Max Born.

The heart of the new theory of quantum mechanics, Born had argued, beats randomly and uncertainly, as though suffering from arrhythmia. Whereas physics before the quantum had always been about doing this and getting that, the new quantum mechanics appeared to say that when we do this, we get that only with a certain probability. And in some circumstances we might get the other.Einstein was having none of it, and his insistence that God does not play dice with the Universe has echoed down the decades, as familiar and yet as elusive in its meaning as E = mc2. What did Einstein mean by it? And how did Einstein conceive of God?

Hermann and Pauline Einstein were nonobservant Ashkenazi Jews. Despite his parents’ secularism, the nine-year-old Albert discovered and embraced Judaism with some considerable passion, and for a time he was a dutiful, observant Jew. Following Jewish custom, his parents would invite a poor scholar to share a meal with them each week, and from the impoverished medical student Max Talmud (later Talmey) the young and impressionable Einstein learned about mathematics and science. He consumed all 21 volumes of Aaron Bernstein’s joyful Popular Books on Natural Science (1880). Talmud then steered him in the direction of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781), from which he migrated to the philosophy of David Hume. From Hume, it was a relatively short step to the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach, whose stridently empiricist, seeing-is-believing brand of philosophy demanded a complete rejection of metaphysics, including notions of absolute space and time, and the existence of atoms.

But this intellectual journey had mercilessly exposed the conflict between science and scripture. The now 12-year-old Einstein rebelled. He developed a deep aversion to the dogma of organised religion that would last for his lifetime, an aversion that extended to all forms of authoritarianism, including any kind of dogmatic atheism.

This youthful, heavy diet of empiricist philosophy would serve Einstein well some 14 years later. Mach’s rejection of absolute space and time helped to shape Einstein’s special theory of relativity (including the iconic equation E = mc2), which he formulated in 1905 while working as a ‘technical expert, third class’ at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. Ten years later, Einstein would complete the transformation of our understanding of space and time with the formulation of his general theory of relativity, in which the force of gravity is replaced by curved spacetime. But as he grew older (and wiser), he came to reject Mach’s aggressive empiricism, and once declared that ‘Mach was as good at mechanics as he was wretched at philosophy.’

Over time, Einstein evolved a much more realist position. He preferred to accept the content of a scientific theory realistically, as a contingently ‘true’ representation of an objective physical reality. And, although…

The post What Einstein meant by ‘God does not play dice’ appeared first on FeedBox.