Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“Life and Reality are not things you can have for yourself unless you accord them to all others,” Alan Watts wrote in the early 1950s, nearly a quarter century before Thomas Nagel’s landmark essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” unlatched the study of other consciousnesses and seeded the disorienting awareness that other beings — “beings who walk other spheres,” to borrow Whitman’s wonderful term — experience this world we share in ways thoroughly alien to our own.

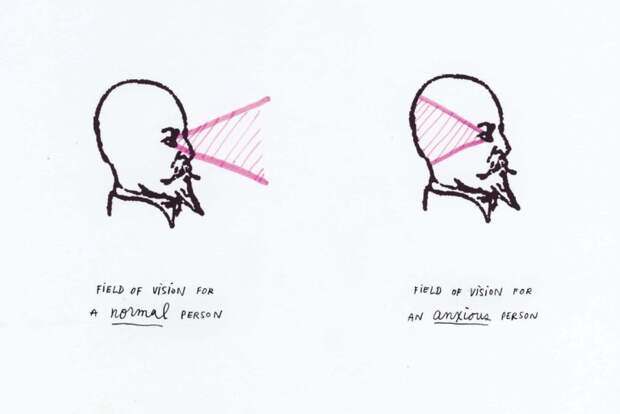

Today, we know that we need not step across the boundary of species to encounter such alien-seeming ways of inhabiting the world.

There are innumerable ways of being human — we each experience life and reality in radically different ways merely by our way of seeing, but these differences are accentuated to an extreme when mental illness alters the elemental interiority of a consciousness. In these extreme cases, it can become impossible for even the most empathic imagination to grasp — not only cerebrally but with an embodied understanding — the slippery reality of an anguished consciousness so different from one’s own. Conversely, it can become impossible for those who share that anguish to articulate it, effecting an overwhelming sense of alienation and the false conviction that one is alone in one’s suffering. To convey that reality to those unbedeviled by such mental anguish, and to wrap language around its ineffable interiority for others who suffer silently from the same, is therefore a creative feat and existential service of the highest caliber.That is what author, Happy Ending Music & Reading Series host, and my dear friend Amanda Stern accomplishes in Little Panic: Dispatches from an Anxious Life (public library) — part-memoir and part-portrait of a cruelly egalitarian affliction that cuts across all borders of age, gender, race, and class, clutching one’s entire reality and sense of self in a stranglehold that squeezes life out. What emerges is a sort of literary laboratory of consciousness, anatomizing an all-consuming yet elusive feeling-pattern to explore what it takes to break the tyranny of worry and what it means to feel at home in oneself.

Part of the splendor of the book is the way Stern unspools the thread of being to the very beginning, all the way to the small child predating conscious memory. In consonance with Maurice Sendak, who so passionately believed that a centerpiece of healthy adulthood is “having your child self intact and alive and something to be proud of,” the child-Amanda emerges from the pages alive and real to articulate in that simple, profound way only children have what the yet-undiagnosed acute anxiety disorder actually feels like from the inside:

Whenever I am afraid, worry sounds itself as sixty, seventy, radio channels playing at the same time inside my head. Refrains loop around and around my brain like fast jabber and I cannot get any of it to stop. I know there is something wrong with me, but no one knows how to fix me. Not anyone outside my body, and definitely not me. Eddie [Stern’s older brother] says a body is blood and bones and skin, and when everything falls off you’re a skeleton, but I am air pressure and tingly dots; energy and everything. I am air and nothing.

[…]

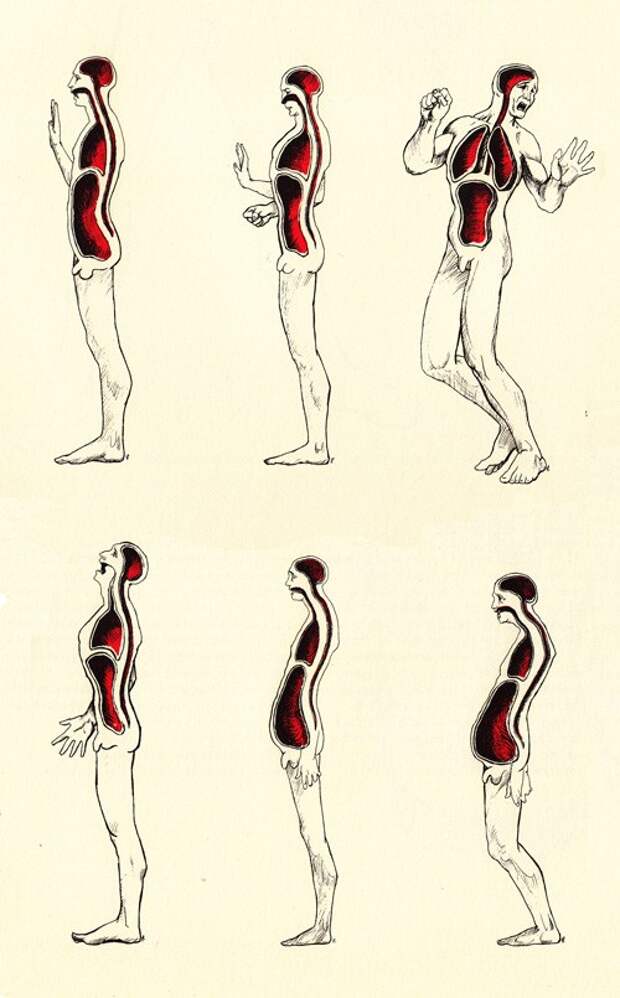

My breath flips on its side, horizontal and too wide to go through my lungs.

The grave paradox of mental illness and mental health is that, despite what we now know about how profoundly our emotions affect our physical wellbeing, these terms sever the head from the body — the physical body and the emotional body. A century after William James proclaimed that “a purely disembodied human emotion is a nonentity,” Stern offers a powerful corrective for our ongoing cultural Cartesianism. Her vivid prose, pulsating with a life in language, invites the reader into the interiority of a deeply embodied mind that experiences and comprehends the world somatically:

A burning clot of dread develops under my ribcage. One hundred radios are trapped in my head, all playing different stations at once.

“I was born with a basketball net slung over my top ribs, where the world dunks its balls of dread,” she writes as she channels her young self’s budding awareness that something is terribly, fundamentally wrong with her:

The kids around me are carefree and happy, but I’m not, and life doesn’t feel easy for me, ever, which means I’m being a kid in the wrong way.

You can’t see the wrong on my outside, but I wish you could because then my mom would get me fixed. My mom can fix anything; she knows every doctor in New York City.

And so Amanda is put through a series of tests. Although she is so small and slight as to be literally off the height and weight distribution chart for children her age, the medical tests fail to find the locus of her anguish:

I am a growing constellation of errors. I don’t know what’s wrong with me, only that something is, and it must be too shameful to divulge, or so rare that even the doctors are stumped.

Psychological tests follow. “Amanda equates performance with acceptability,” one clinician reports in the original test results punctuating the book like some ominous refrain of wrongness. Then there are the IQ tests. Growing up in an era well before scientists came to understand why we can’t measure so-called “general intelligence,” well before Howard Gardner revolutionized culture with his theory of multiple intelligences, the young Amanda does poorly on the tests — lest we forget, test-taking itself is an immensely anxiety-inducing act even for the average person unafflicted by a panic disorder. Deemed learning-disabled and held back a grade, she reanimates that first school day of her second second year in sixth grade:

The air is fresh, the slight coolness in front of each breeze carrying the…

The post Little Panic: A Literary Laboratory Exploring What It Is Like to Live in the Stranglehold of Anxiety and What It Takes to Break Free appeared first on FeedBox.