Author: Paula Mejia / Source: Atlas Obscura

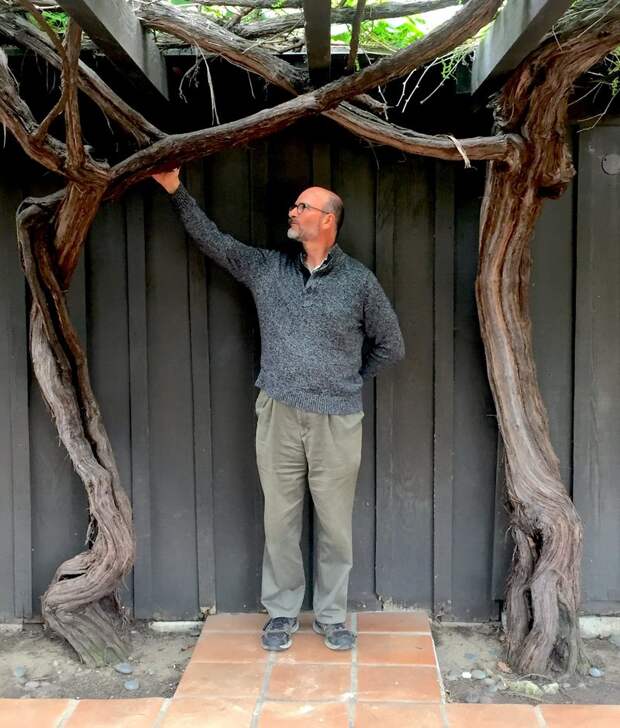

Mike Holland, a bespectacled home winemaker, often arrives downtown several hours before starting his day job, at the Los Angeles City Archives. Before the sun rises over the Avila Adobe on Olvera Street— built in 1818, and considered to be the oldest home in the city—Holland will perch on a ladder pruning, trimming, and managing a tangle of leaves.

His goal is to gather as many of these minuscule grapes as he can before 9 a.m., the Adobe’s opening time.These aren’t your ordinary vines. Years ago, Holland, whose office is located near the Adobe, had been taken with these unusual vines, which lurch skywards and through a main artery in the building. He was curious, and offered to care for them, and make wine out of them. To find out more about their origins, he sent cuttings to the Foundation Plant Services at the University of California, Davis, whose staff came back with astonishing news: The vines were a hybrid between a local grape and a European grape, and they genetically matched what’s now known as the Viña Madre, or the “mother vine” grape that grew at the nearby Mission San Gabriel.

That meant that Holland had stumbled upon a relic, a vine that was perhaps the first in California to produce grapes to make wine. Since then, Holland has been using these grapes to make a special sherry-like wine, called Angelica, that has its origins in Southern California, too. It’s one of the sole remnants of a time when vineyards covered downtown Los Angeles.

Long before a maze of highways spliced through the city—preceding the cluster of gleaming skyscrapers that tower above downtown, as if making eye contact with the mountains—vineyards enveloped the now-urban center.

Throughout the 19th century, many acres of grapevines grew right where contemporary landmarks, such as the Bradbury Building (seen in many films) and the Angels Flight now stand. Back then, Los Angeles was not only the birthplace of California wine country, but its beating heart, too.

Before California even became part of the United States, it was Los Angeles—not Sonoma, not Napa—that was poised to become the winemaking epicenter of the west coast. So much so that by 1850, the Los Angeles area boasted over 100 vineyards, and the city’s first-ever seal, drawn up several years later, dubbed it the “city of vines.” So how is it that L.A.’s northern neighbors won California’s winemaking crown, while the city’s own history as a land of vines faded into obscurity?

“It’s more of a tale of urbanization, unfortunately,” says Steve Riboli, who helps oversee winemaking operations at San Antonio Winery. Built in 1917 by Riboli’s great-great-uncle Santo Cambianica, an Italian immigrant, San Antonio is the last surviving downtown Los Angeles winery. The timing was unfortunate—as it was built three years before Prohibition—but a local church allowed Cambianica to make sacramental wine, one of the loopholes during that dry era. “We were able to survive because he was a very devout Catholic,” Riboli says.

Before then, basement to full-fledged operations flourished in the area. But continuous population booms, especially during the Gold Rush era, both helped build and ultimately ended L.A.’s winemaking prospects.

The city’s history as a wine town started when California was colonized by the Spanish. Spaniards enjoyed drinking wine and Franciscans used it in religious ceremonies. One of the missionaries sent there, Father Junipero Serra, had grape cuttings sent up from Mexico in 1778 and began to produce sacramental wine. The vines thrived at Mission San Gabriel, a skip away from present-day Los Angeles.

Around then, wine production in Los Angeles began picking up. Winemaking wasn’t a commercial prospect for the region until a Frenchman,…

The post The Gnarled History of Los Angeles’s Vineyards appeared first on FeedBox.