Author: Erica Naone / Source: Atlas Obscura

Captain John Smith is perhaps best known for his (possibly fictional) encounter with Pocahontas.

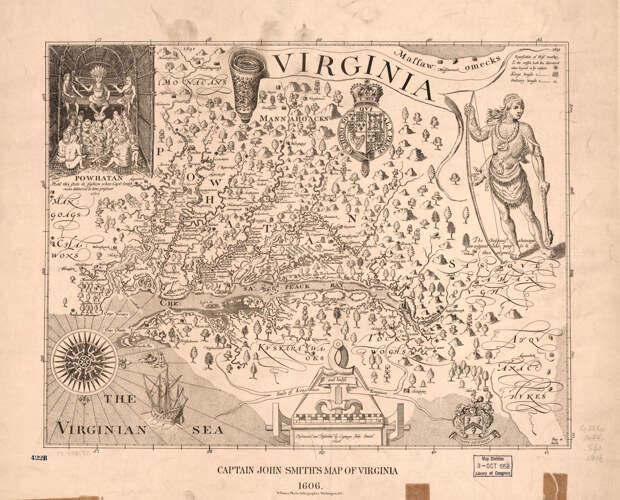

Whatever the true nature of that meeting was, the British explorer distilled his explorations and meetings with the indigenous people of what is now Virginia into a remarkable map that defined European impressions of the region for the majority of the 1600s.Widely considered a masterpiece, Smith’s map is dominated by artistic renditions of the indigenous people of the region, especially Powhatan, the powerful leader of at least 30 Algonquin-speaking tribes in the Chesapeake Bay area, including the Potomac, the Chesapeake, the Mattaponi, and the Secacawoni. On Smith’s map, Powhatan is the name of a man, a region, and the river that European settlers would rename the James.

If Smith’s Virginia looks unfamiliar to the modern viewer, it’s not only due to the extensive territory held by indigenous people. Smith drew his map with west at the top and north pointing to the right, spreading the land out the way it might have appeared to a European ship captain landing on the mid-Atlantic coast.

Orienting maps toward the west this way has always been rare. Though mapmaking conventions, such as standard orientation and use of latitude and longitude, still hadn’t fully formed by the early 17th century when Smith’s map was published, maps showing north at the top were already common. According to Matthew Edney, a professor of geography and cartography at the University of Southern Maine, by 1600, most regional and commercially produced maps were oriented toward the north.

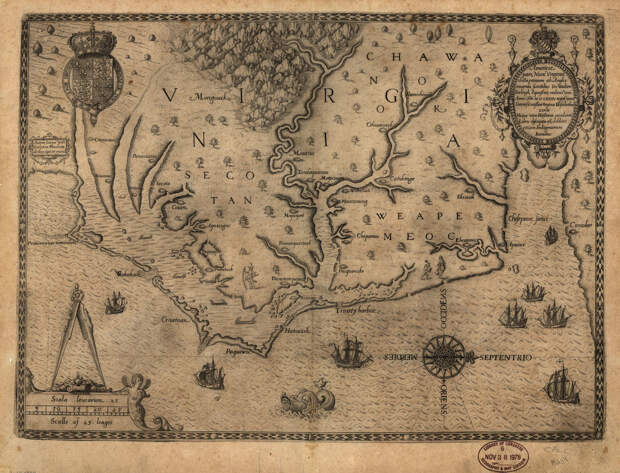

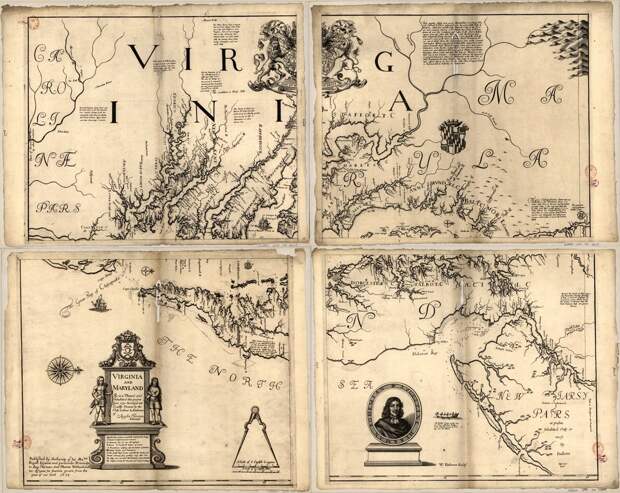

However, many Virginia maps of the 17th century mirror the orientation of Smith’s. These include Augustine Herrman’s Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670; John Lederer’s A map of the whole territory traversed by John Lederer in his three marches; and John Ferrar’s A map of Virginia discovered to ye falls. Some scholars see meaning in the decision to draw these maps with west at the top. The viewpoint of the map, after all, could reveal something about the viewpoint of the mind.

“Maybe it’s about an invitation more than a geography lesson,” says Buck Woodard, a lecturer in the department of anthropology at American University. He notes that many maps of the era were used in part to encourage Europeans to travel to North America as settlers.

Woodard points out that British explorers of the time also drew maps of Ireland with west at the top. In both cases, the British were in the process of conquering territory and establishing settlements. “When there’s a colonial interest, the map is oriented for your arrival,” he says.

But this isn’t the only theory about the unusual orientation of this set of maps. Edney wonders if the orientation toward the west is geared in part toward the European explorers’ desire to establish an easy sea route to China. The maps’ viewpoint could be a way of looking past this land and toward the sea they hoped to discover just beyond.

Or it’s possible that the maps are oriented to make the most of the cartographers’ knowledge, Edney says. European explorers did not know what lay beyond a certain westward…

The post In Early Maps of Virginia, West Was at the Top appeared first on FeedBox.