Author: Eveline Chao / Source: Atlas Obscura

Ricardo Hoyen likes to joke that he was kidnapped. He was born in Jamaica, where he grew up in Kingston, but was sent to New York City to live with an aunt when he was 15, in 1964.

“I thought I was coming to visit the World’s Fair,” he says. “I didn’t know it was to stay.”In New York, Hoyen (who goes by the nickname Ricky) attended the High School of Commerce, located where Lincoln Center now stands. “I was accused of not speaking English because they couldn’t understand my accent,” he recalls. ”And when I said I was from Jamaica one of my teachers called me a liar.” (Hoyen also has black and European ancestry, through a French-Cuban grandmother, but is usually perceived as Chinese.) The fervor of the sixties was in full swing, and Hoyen plunged in: protesting the Vietnam War, frequenting jazz clubs, traveling south to march against the KKK, and dabbling in Harlem’s black nationalist scene, among the followers of Marcus Garvey.

Through it all, he pined for Jamaica. He often made an effort to seek out other Chinese Caribbeans, many of whom who worked in restaurants and bakeries throughout Harlem, Crown Heights in Brooklyn, and Chinatown. Like Hoyen, those people were part of a larger wave of diaspora who left the Caribbean throughout the 1960s,‘70s, and ‘80s, and now live elsewhere around the world. “I say I was kidnapped because life was wonderful in Jamaica,” Hoyen says.

“If you had ever lived there, you would never want to leave.”Lately, the search for connection to his past has taken Hoyen to a new semi-annual gathering called the New York Hakka Conference, the local version of many such conferences around the world. Most Chinese who, like both of Hoyen’s grandfathers, migrated from Southern China to Jamaica throughout the 19th or early 20th century were Hakka, a group of people originating in China with a distinct set of customs and a language also called Hakka. Because of that, and because the New York Hakka Conference is organized by a woman with ties to Jamaica, the event has become a magnet for not only the usual dispersed Chinese Hakka who attend such events , but in particular for Afro-Chinese-Caribbean people who wish to learn more about their roots. The vagaries of personal relationships, the great geographic distances that members of the Chinese and Afro-Caribbean diaspora have traversed, and the twists and turns of history have meant that many such families have become separated. But some of them are looking to reconnect.

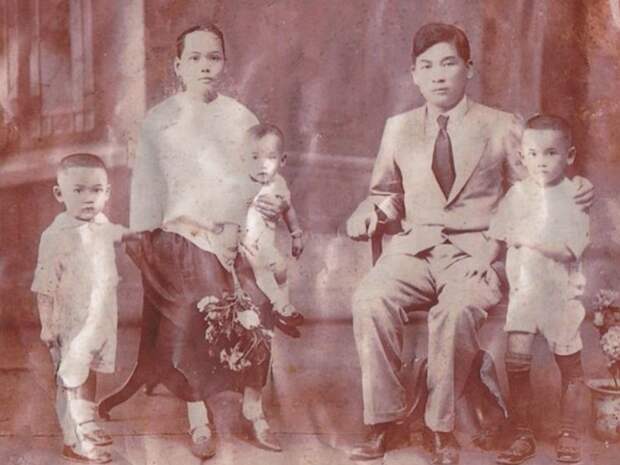

Paula Madison, the 65-year-old organizer of the New York Hakka Conference, grew up in Harlem always wondering about her Chinese grandfather, Samuel Lowe. All she knew was that he had migrated to Jamaica in 1905, established several general stores, and had Madison’s mother, Nell Vera Lowe, with a local Afro-Jamaican woman named Albertha Campbell in 1918. The couple split up when Nell was three, after Samuel Lowe said he was betrothed to a Chinese woman who was coming to Jamaica, and that he wanted to raise the child with his Chinese wife. Albertha refused, and Nell never saw her father again. When Nell was 15, she traveled to the town where his store was, and learned that he had moved back to China , after trying unsuccessfully to find her. Madison speculates he left due to a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment that flared up in Jamaica during the 1930s. His brothers, who were still in Jamaica, gave Nell a pair of pearl earrings he had left behind for her.

Nell eventually moved to the United States, where she died in 2006. But in 2012, Madison was able to track down her grandfather’s ancestral village and burial site in China, thanks to a Hakka conference she attended in Toronto. (A large proportion of Chinese Jamaicans who left the island during the 1960s and ‘70s resettled in Toronto.) During the conference, Paula approached the organizer, Jamaican-born Keith Lowe, because of his last name, and several cross-continental phone calls and emails later, the two figured out they were distant cousins from the same ancestral village in China. Madison has now gained 300 new Chinese relatives, whom she visits several times a year. She also boasts that she has…

The post The Caribbean-Americans Searching for Their Chinese Roots appeared first on FeedBox.