(Image credit: Flickr user Craig Dietrich)

California’s third-largest city by area is an urban-planning disaster, a sprawl of empty grids that aspired to become a megacity—and failed. But as the desert works to reclaim the land, it’s become a mecca of another kind.

It was June in the Mojave desert and the sun was blistering. The land around me was empty, scorched, and flat, dotted by brush and the occasional piece of windswept trash. Judging by the map, the intersection where I’d stopped was a busy crossroads between two major thruways. But when I shifted into park in the middle of the road, no one honked. No one looked at me funny. I hadn’t seen another car in an hour at least.

It was probably the safest intersection in America to pull over and take a nap.

According to the map, I was surrounded by cul-de-sacs and neighborhoods. In reality, there was nothing but sand and more sand—and roads. Endless roads. Roads in all directions, marked by white fence posts and the occasional lonely pole. Some were paved. Some were dirt. Some had long ago been reclaimed by the encroaching sand.

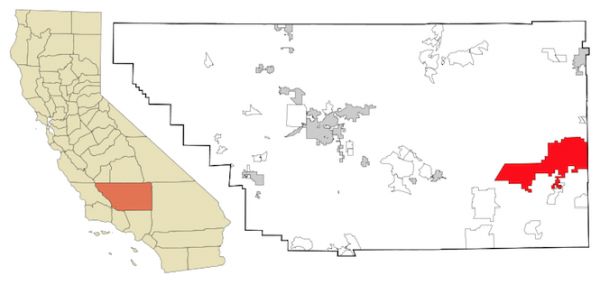

California City, California, is the third-largest city by area in America’s third-largest state, and most of it barely even qualifies as a ghost town—a ghost town needs people to have lived there first.

California City is a ghost grid.

(Image credit: Google Earth)

That afternoon, it was 98 degrees. Bugged out by the isolation, I kept thinking about everything I didn’t know how to fix if something went wrong with my car.

I checked my phone in case I needed to call AAA: no reception. I shaded my eyes with my hand. In the near distance were two hulking wrecks, old cars like two relics of a previous era. The 14,000 or so people who do live in California City were miles behind me, in a concentration of ranch homes and stores clustered around the main drag. Out here, the only evidence of life was a half-dozen RVs I’d spotted, circled like wagons, and two dirt bikes I saw cresting a hill.A hundred yards away, I spotted a mini tornado kicking up sand, whirling straight toward me. Time to go. I jumped back in the car, shifted into drive, and hit the gas—and 30 seconds later, plunged the nose of my Honda Accord off the lip of a three-foot drop.

Who put a sand dune there?

The history of California City is one of fever, fervor, and near-bust. Even today, it’s a town of weird contrasts. Two hours north of Los Angeles, in the Antelope Valley, the town takes up 204 square miles of land. In California, going by total acreage, only L.A. and San Diego are bigger. But the city’s population makes it one of the state’s smaller towns.

Of course, the founding dream was much more grandiose. Nathan K. Mendelsohn, a Czech immigrant, taught sociology at Columbia University in the 1940s before he moved west with big ideas about developing communities in California. Mendelsohn was a visionary, a dreamer. Prior to California City, he worked with famed real estate developer M. Penn Phillips, who helped build California’s Salton City—a resort community that was practically built out of nothing, only to collapse at the end of the ’70s.

In 1958 Mendelsohn, working with investors, bought 82,000 acres of land in the desert to develop a metropolis. The idea was to build a community that would join the ranks of America’s great cities, even outdo them. Mendelsohn and colleagues drew plans, cut roads. Streets were named after the country’s best universities, its biggest car manufacturers: Stanford, Yale, Pontiac, Cadillac. He built a park in the center of town named Central Park, and even included a man-made lake. When it came time to fill it, he flew in water from New York’s Upper West Side.

(Image credit: Arkyan)

The radio jingle for the town said it all: “Buy a piece of the Golden State;You’ll be sitting pretty when you come to California City.” People could buy a vacant lot for $990. Three-bedroom homes went for less than $10,000. “There was a kind of buying hysteria up there,” Carl Click, an optometrist, would later recall to the Los Angeles Times. Believing that California City would soon be bustling, many landowners paid for property hoping to get a big return on their investment in just a few years. Buses of people would arrive regularly to look around. Mendelsohn himself donated a small church and a city airport. He offered land to corporations for $1 an acre—if they would build a plant and provide jobs.

Cities are not often created out of nothing. Damascus, one of the world’s oldest cities, had from the beginning an oasis to farm, a river to drink from. In the United States, the early 1700s saw a diminutive island called Manhattan become an important global trading port. “When Mendelsohn first pitched California City, he saw it as a rival to L.A., even bigger than L.A.,” said Geoff Manaugh, the futurist and architectural writer. “It was inspired by the greater sprawl of L.A., to make something even bigger.”

To lots of people, sprawl is a dirty word. It sounds like a real estate–transmitted disease. But in many parts of America—Southern California, the urban West, the cities of the Southeast and Texas—it’s how communities grow. Sprawl-wise, though, California City didn’t stand a chance. Thousands of lots were sold,…

The post A California Dream appeared first on FeedBox.