Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

When British archaeologist Howard Carter cracked into Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, he was dazzled by the contents—“Gem-Studded Relics in Egyptian Tomb Amaze Explorers,” The New York Times declared—but he wasn’t especially impressed by its walls. The resting place of the young ruler is humble compared to others in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings—four rooms occupying 9,762 cubic feet, less than a quarter of the size of the burial site of Ramesses V and VI.

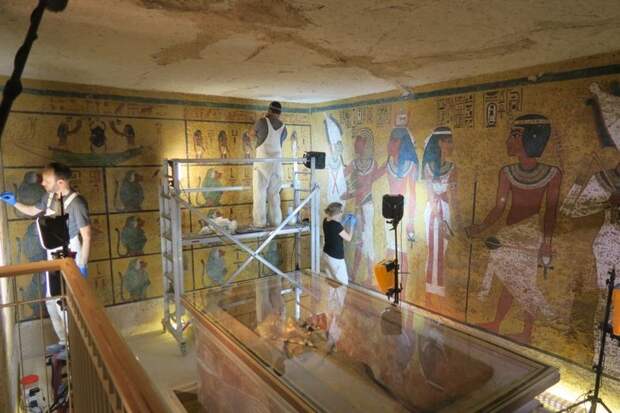

Conservators have remarked that the paintings on the thin clay plaster covering the rough-cut walls of the burial chamber show numerous drips and other signs of haste; the tomb was likely prepared quickly, since the ruler died young. Carter once characterized the scenes depicting Tut’s funeral procession and the journey of his successor, Ay, as “rough, conventional, and severely simple.”Tourists haven’t seemed to mind the rush job on the walls—in fact, they have been utterly entranced. Just before the 2011 Egyptian revolution, several hundred people per day squeezed into the confined spaces. Each and every one of those visitors had inconvenient but unavoidable habits: namely, breathing and sweating. In those cramped subterranean quarters, moisture is the enemy.

Visitors can mean all sorts of trouble for historic sites. Footsteps can quake fragile, old structures, and people have a tendency to leave behind scribbled musings and wads of gum. Even the lightest-trodding, most respectful visitor presents passive problems. In Tut’s tomb, “visitors increase relative humidity, elevate carbon dioxide levels, and along with natural ventilation into the tomb, promote the entry of fine airborne particles,” wrote researchers, led by the Getty Conservation Institute’s Lori Wong, a wall paintings expert, in a 2018 paper in Studies in Conservation.

In partnership with Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities, Getty conservators just wrapped a nearly decade-long conservation project to guard the tomb against the impact of heavy-breathing, heavy-sweating visitors.

(The tomb remained open to the sweaty masses nearly the whole time.) Before they began, the team had to quantify just how bad the problem was. The researchers installed a suite of monitors to track air temperature, relative humidity, carbon dioxide concentration, and other environmental factors. In 2009—the first year of data collection—relative humidity inside peaked at 70 percent in September, one of the desert’s most sweltering months. (Meanwhile, humidity averaged less than half of that just outside the tomb.) The mean temperature indoors hovered around 80 degrees Fahrenheit all year long; National Geographic once described the environment inside as “almost tropical.” It was impossible to pin down the precise levels of carbon dioxide because the air in there routinely maxed out the sensor, which went up to 3,500 ppm—roughly ten times higher than the concentration outside, according to conservators.It wasn’t a pretty picture. Visitors brought in dust that fell like snow on the glass case holding Tut’s sarcophagus. On the wall paintings, the dust made the humidity problem more troublesome, because it could “encourage moisture uptake, damaging paint layers, and can cement itself to the surfaces, making it difficult to remove,” the authors wrote. Fluctuating humidity levels—seasonally or over the course of a day—can cause the plaster beneath the paint to expand and contract, threatening the integrity of the painted scenes. Carbon dioxide wasn’t a concern for the wall paintings, but rather “a serious contributory factor to visitor health and comfort,” says Neville…

The post Our Breath and Sweat Almost Ruined King Tut’s Tomb appeared first on FeedBox.