Author: Dan Maloney / Source: Hackaday

We humans are good at a lot of things, but making holes in the ground has to be among our greatest achievements. We’ve gone from grubbing roots with a stick to feeding billions with immense plows pulled by powerful tractors, and from carving simple roads across the land to drilling tunnels under the English Channel.

Everywhere we go, we move dirt and rock out of the way, remodeling the planet to suit our needs.Other worlds are subject to our propensity for digging holes too, and in the 50-odd years that we’ve been visiting or sending robots as our proxies, we’ve made our marks on quite a few celestial bodies. So far, all our digging has been in the name of science, either to explore the physical and chemical properties of these far-flung worlds in situ, or to actually package up a little bit of the heavens for analysis back home. One day we’ll no doubt be digging for different reasons, but until then, here’s a look at the holes we’ve dug and how we dug them.

The Moon

For the purposes of this article, I’m going to just discuss the times that missions have intentionally dug, drilled, or blasted holes in celestial bodies for the purpose of exploration. This leaves out important but purely symbolic acts of excavation, like leaving footprints and planting flags on the Moon. It also excludes all of the dozens of times spacecraft were intentionally or accidentally crashed into things. Many such early missions to the Moon ended that way, with the first being the Luna 2, a Soviet mission that impacted in September of 1959, less than two years after Sputnik.

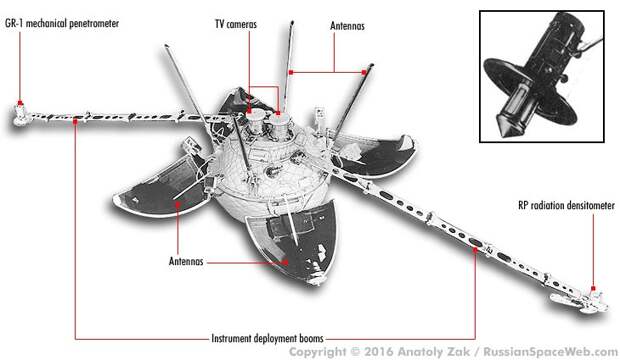

It wouldn’t be until late December of 1966 that the first craft designed to dig a hole would land on the Moon. Luna 13‘s mission was to assess the suitability of the lunar surface for a manned Soviet landing that would never come. The main instrument was a penetrometer, attached to the end of a long boom deployed after landing. The instrument had a short rod with a sharpened tip and a small solid-propellant rocket motor to drive it down into the lunar surface. It penetrated 45 cm into the regolith and measured the density and consistency of the soil.

That first human-made hole in the Moon was followed four months later by Surveyor 3, one of a series of American probes designed to find suitable locations for landing the planned Apollo missions. The lander carried a Soil Mechanics Surface Sampler (SMSS), and extendible pantograph arm with a small soil scoop on the end. The arm had azimuth and elevation control motors in its base, allowing it to range in a wide arc, and telemetry allowed engineers to infer the forces on the regolith from the current drawn by the motors. The SMSS was very busy for 18 hours, controlled in near real-time through the lander’s slow-scan TV camera. It dug multiple trenches, pressed down on the lunar surface, and did impact tests by dropping the scoop from a height. It even picked up a rock and tried to crush it; sadly, the scoop didn’t have enough oomph for that.

Subsequent Surveyor missions also gathered SMSS data, sufficient to be reasonably sure the Apollo missions would be able to land safely and return with samples from the Moon’s surface. Apollo 11 was the first successful sample return mission, and returning samples from the Moon was considered so important by mission planners that one of…

The post Extraterrestrial Excavation: Digging Holes on Other Worlds appeared first on FeedBox.