Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

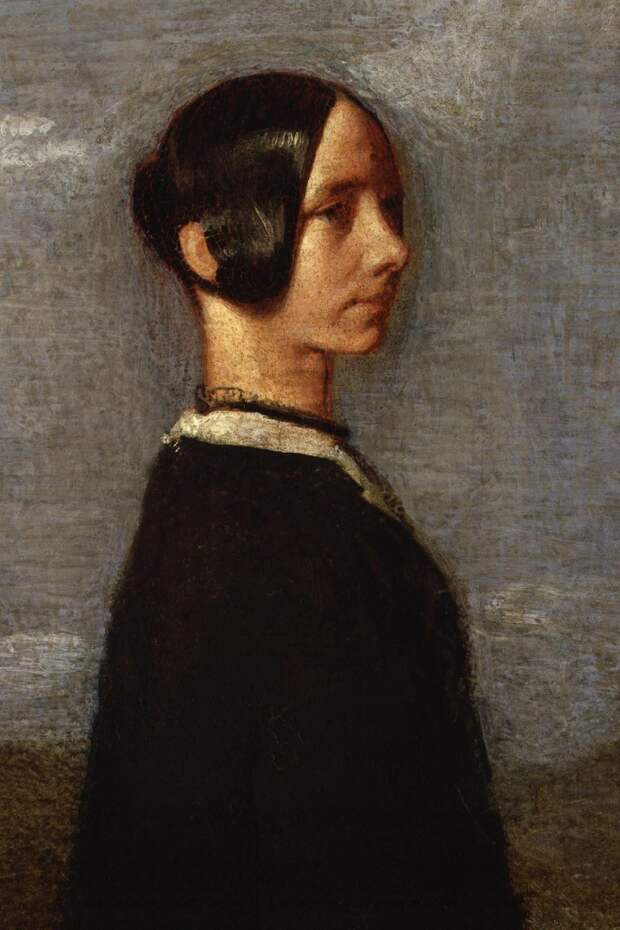

Like Alice James — the brilliant diarist who lived and wrote in the shadow of her brothers, Henry and William James — Jane Welsh Carlyle (January 14, 1801–April 21, 1866), unpublished and shadowed by her famous husband, was a literary genius whose private letters stand as masterpieces of prose in their own right.

Virginia Woolf admired her as “so brilliant, so deeply versed in life and scornful of its humbugs… the most caustic, the most concrete, the most clear-sighted of women.” Charles Dickens considered her a greater storyteller, with a superior talent for observation and character development, than any of the published women novelists of her day. For a time, she was rumored to have authored the pseudonymously published Jane Eyre.What lent her letters their shimmering intensity of insight was Jane’s uncommon openness to and insight into the complex, often confusing inner workings of the human heart and is maddening contradictions.

Shortly after her twentieth birthday, Jane Welsh met Thomas Carlyle — the essayist, mathematician, historian, and philosopher, who was then a struggling young writer of lower social stature, with no stable income and no intellectual achievement to his name, but would later become Scotland’s most esteemed polymath. At first, she spurned his courtship with the adamant insistence — perhaps out of self-knowledge, perhaps out of self-protection and fear — that she is constitutionally incapable of romantic love, uninterested in marriage at the expense of her intellectual ambitions, and would only hurt him if she consented to a relationship. In a letter from early 1823, found in the devastatingly titled I Too Am Here: Selections from the Letters of Jane Welsh Carlyle (public library), she pushes him away with equal parts magnanimity toward his needs and uncompromising clarity about hers:

To cause unhappiness to others, above all to those I esteem, and would do anything within my duties and abilities to serve, is the cruelest pain I know — but positively I can not fall in love — and to sacrifice myself out of pity is a degree of generosity of which I am not capable — besides matrimony under any circumstances would interfere shockingly with my plans.

Carlyle, conflicted in his own right at the prospect of getting hurt but besotted nonetheless, plays into this game of push and pull, charging that it is “useless and dangerous” for him to love her and that she has made his “happiness wrecked” by letting him fall in love with her and then rejecting him. Jane responds by insisting that her love for him is true, but not the kind he yearns for. In the last week of summer, she grows even more resolute in her dual pledge that she will never leave him as a friend but will never be with him as a romantic partner:

My Friend I love you — I repeat it tho’ the expression a rash one — all the best feelings of my nature are concerned in loving you — But were you my Brother I would love you the same, were I married to another I would love you the same — and is this sentiment so calm, so delightful — but so unimpassioned enough to recompense the freedom of my heart, enough to reconcile moe to the existence of a married woman the hopes and wishes and ambitions of which are all different from mine, the cares and occupations of which are my disgust — Oh no! Your Friend I will be, your truest most devoted friend, while I breathe the breath of life; but your wife! never never!

But then, having issued this most vehement of self-protective disclaimers, she adds:

Write to me and reassure me — for God’s sake reassure me if you can! Your Friendship at this time is almost necessary to my existence. Yet I will resign it cost what it may — will, will resign it if it can only be enjoyed at the risk of your future peace — …

They continued this conflicted dance for more than a year, until it became clear they had to make a choice. In a letter penned in the first days of 1825, a week before Jane’s twenty-fourth birthday, she confronts the abiding question of how you know whether you are in love, as opposed to merely infatuated:

I love you — I have told you so a hundred times; and I should be the most ungrateful, and injudicious of mortals if I did not — but I am not in love with you — that is to say — my love for you is not a passion which overclouds my judgement; and absorbs all my regards for myself and others — it is a simple, honest, serene affection, made up of admiration and sympathy, and better perhaps, to found domestic enjoyment on than any other — In short it is a love which influences, does not make the destiny of a life.

Jane had two primary reservations about marrying Carlyle: that their differences — of class, of means, of ambitions — were too vast, and that a life of domesticity would keep her from actualizing herself as a writer. Asserting that “the idea of a sacrifice should have no place in a voluntary union,” she suggests that marrying him would be a self-sacrifice — a form of settling for a life smaller than the life she wants. And yet she also acknowledges that her choice is not between marrying him and marrying someone else, but between marrying him and not marrying at all. She writes:

I should have goodsense enough to abate something of my romantic ideal, and to content myself with stopping short on this side idolatry — At all events I will marry no one else — This is all the promise I can or will make. A positive engagement to marry a certain person at a certain time, at all haps and hazards, I have always considered the most ridiculous thing on earth: it is either altogether useless or altogether miserable; if the parties continue faithfully attached to each other it is a mere ceremony — if otherwise it comes a galling fetter riveting them to wretchedness and only to be broken with disgrace.

She presents him with her take-it-or-leave-it proposition: If their love is to endure, it must not be rushed into marriage but allowed to grow organically, its rightness and resilience tested in the garden of time:

Such is the result of my deliberations on this very serious subject. You may approve of it or not; but you cannot either persuade me or convince me out of it — My decisions — when I do decide — are unalterable as the laws of the Medes & Persians — Write instantly and tell me that you are content to leave the event to time and destiny and in the meanwhile to continue my Friend and Guardian which you have so long and so faithfully been — and nothing…

The post Loving vs. Being in Love: Jane Welsh Carlyle on Navigating the Heart’s Contradictions appeared first on FeedBox.