Author: Daniel Crown / Source: Atlas Obscura

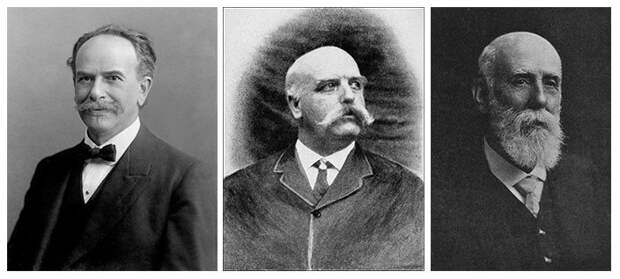

In 1896, New York City’s American Museum of Natural History hired Franz Boas, a notable anthropologist and curator, to spruce up its growing-but-inadequate collection of ethnographic materials.

At the time, the institution boasted numerous Native American artifacts, but had a limited collection of similar objects from around the world. Boas, now considered the founder of American anthropology, jumped at the opportunity to curate specific and well-defined collections that effectively captured the complicated global history of human development.Boas was uniquely qualified to achieve this goal. Having already served in similar roles at Chicago’s Field Museum and Berlin’s Royal Museum for Ethnology, he understood the cardinal rule of late-19th century curation: What you couldn’t get in the field, you traded for. It’s not surprising, then, that when he set out to assemble materials from Indigenous Australians in April 1899, he reached out to Roger Etheridge, curator at the Australian Museum in Sydney, looking to strike a deal.

That month, he wrote to the museum requesting carefully curated artifacts from a single but non-specified group of Aboriginal people. His opening move in these negotiations would have fit right in a century later amid a front-porch trading card swap: he offered Etheridge his dupes. “Our museum is very strong in collections from the Pacific coast of America and from arctic America,” Boas wrote, “and it would be possible to arrange a good typical collection from either or both regions for purposes of exchange.

”Etheridge initially rejected the offer. While his institution owned several of the weapons and tools Boas desired, he could not relinquish them “for the want of duplicates.” Still, Etheridge hoped the museums could come to different terms. “If your Museum is desirous of Marsupial skins,” he responded in May, “a fairly good set, either mounted or in skin, could be sent in exchange for the works of the American Aborigines.”

From a 21st-century vantage, it’s hard to fathom prominent museums swapping stone axes and kangaroo skins as if they were Pokémon; however, according to Catherine Nichols, a lecturer in cultural anthropology and museum studies at Loyola University Chicago, this exchange between Boas and Etheridge perfectly encapsulates the common practice in their era of swapping duplicates—items Nichols defines as “a kind-of-thing” of which a museum already owned enough representative examples “to serve scientific and educational purposes.” Museums usually considered a “kind of thing” a specific item from a distinct region, species, or people—a Zuni vase for instance, or a Zande spear-head. If a museum owned enough examples of one of these vases or spears, it labeled excess artifacts as duplicates.“Almost all museums exchanged duplicates in the late-19th and early-20th centuries,” Nichols says. “Every exchange was different to a point, but people were often trying to fill gaps in their collections. So, if an institution didn’t have specific material, and it knew a different museum did, it would write and ask about duplicates.”

According to Nichols—who unearthed many of the exchanges detailed in this article amid her extensive research on the subject—19th-century museums saw nothing unethical in this behavior. Most ethnographic items were originally procured either through bartering directly with indigenous peoples or through funded excavations. Curators like Boas and Etheridge believed the transparent nature of these methods cleared them of any ethical grey area, even when exchanging culturally sensitive items.

Indeed, examples of these exchanges abound in the records kept by most major museums. Curators from across the world often reached out to one another with wish lists, alongside inventories of surplus items available for one-off trades. Some even established decades-long trading relationships, thereby creating a global network that saw the exchange of countless artifacts, ranging from contemporary animal specimens to the skulls of ancient Romans.

According to Nichols, this network effectively established duplicates as a world-wide currency among anthropologists, zoologists, and archaeologists. Its existence caused museums of the era to expand purchase and expedition efforts to include the procuration of excess artifacts they could swap for items on lists often referred to as “desiderata.” For example, says Nichols, “if a museum was going to send an expedition to the Philippines, it would collect more than it ultimately needed, because it knew that if it collected multiple examples of something, it could trade…

The post 19th-Century Museums Swapped Priceless Artifacts Like Trading Cards appeared first on FeedBox.