Author: Lisa Grossman / Source: Science News

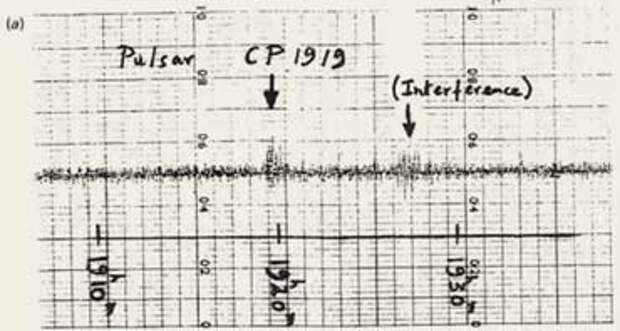

Jocelyn Bell Burnell first noticed the strange, repeating blip in 1967.

A University of Cambridge graduate student at the time, she had been reviewing data from a radio telescope she had helped build near campus. Persistent tracking revealed the signal’s source to be something entirely unknown up to that point — a pulsar, or a rapidly spinning stellar corpse that sweeps beams of radio waves across the sky like a lighthouse.A half-century later on September 6, Bell Burnell was awarded the $3 million Special Breakthrough Prize in fundamental physics. The prize has been given only three times before: to British physicist Stephen Hawking for discovering a type of radiation from black holes in 1974, the CERN team that discovered the Higgs boson in 2012, and the LIGO collaboration that in 2016 found gravitational waves.

But before any of those discoveries, Bell Burnell’s pulsar find was revolutionizing astrophysics. It led to precise tests of Einstein’s theory of gravity, the first observations of exoplanets and the 1974 Nobel Prize in physics — from which Bell Burnell was famously excluded. Now 75 years old, Bell Burnell is giving back, donating her prize to create scholarships for underrepresented minorities in physics and astronomy.

Science News caught up with Bell Burnell to chat about aliens, impostor syndrome and how being an outsider can be a boon in scientific research.

The following answers have been edited for length and clarity.

J.B.B.: It was an anomaly, and it was a very small anomaly. Typically it took up about 5 millimeters of my long rolls of chart paper, out of half a kilometer. I was being very, very thorough, very careful. I kept poking at it to try and understand what it was.

SN: You called the first signal LGM-1, for Little Green Man 1. Did you really think it might be a signal from aliens?

J.B.B.: That was a bit of a joke, which I now rather regret. But we did check it out. My advisor Tony [Hewish] argued that, if it were little green men as we nicknamed them, they’d probably be on a planet going round their sun. As their planet moved, we would see what’s called Doppler shift. The spacing between pulses would change as their planet moved. We looked for that, but we couldn’t find any such motion.

SN: At what point did you realize that pulsars were going to be a big deal?

J.B.B.: Quite late in the process. I’d found all four that I was going to…

The post Jocelyn Bell Burnell wins big physics prize for 1967 pulsar discovery appeared first on FeedBox.