“What you see in a total eclipse is entirely different from what you know.”

“A writer is someone who pays attention to the world — a writer is a professional observer,” Susan Sontag wrote in contemplating the project of literature. Often, the measure of a writer is the attentiveness with which they observe the subtlest dimensions of existence, those realms of experience imperceptible to the eye.

Sometimes, it is the subtlety and nuance with which they capture the human dimensions of the most dramatic observable phenomena, the ones that arrest the eye and overwhelm the ordinary mind into a stunned silence.A century after pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell penned her enchanting and rhetorically ingenious account of the Great Eclipse of the nineteenth century, Annie Dillard — another enchantress of observation, a supremely poetic observer of phenomenology inner and outer — captured the otherworldly experience of a total solar eclipse in a stunning essay originally published in her 1982 book Teaching a Stone to Talk, then included in her indispensable recent collection The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old and New (public library | IndieBound).

Dillard frames the inescapable cosmic drama of this divinely disorienting experience:

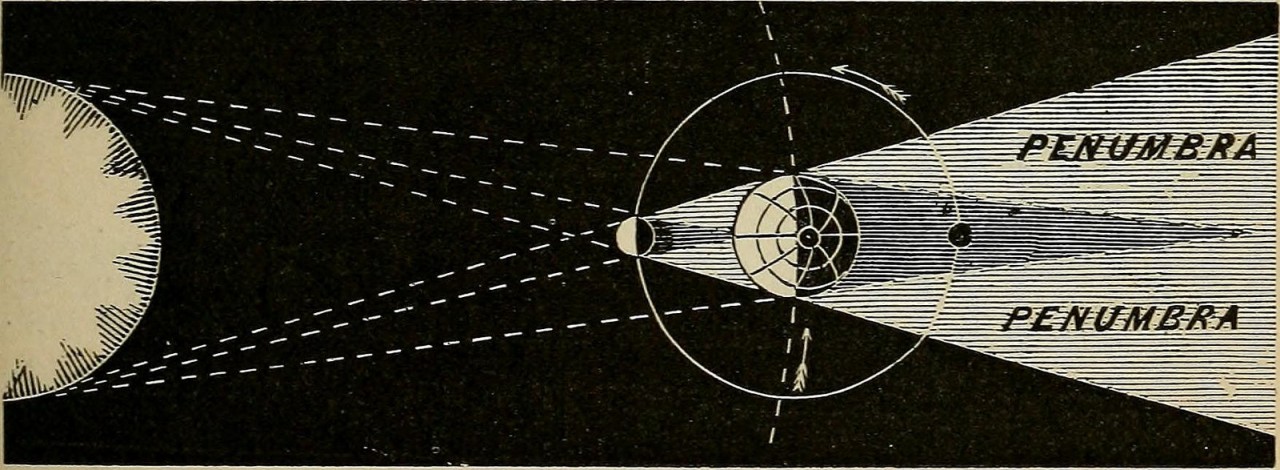

What you see in a total eclipse is entirely different from what you know. It is especially different for those of us whose grasp of astronomy is so frail that, given a flashlight, a grapefruit, two oranges, and fifteen years, we still could not figure out which way to set the clocks for daylight saving time.

Usually it is a bit of a trick to keep your knowledge from blinding you. But during an eclipse it is easy. What you see is much more convincing than any wild-eyed theory you may know.

Recounting her own experience of viewing the total solar eclipse of March 26, 1979, she paints the eerie landscape of sight and sense:

The sky’s blue was deepening, but there was no darkness. The sun was a wide crescent, like a segment of tangerine. The wind freshened and blew steadily over the hill. The eastern hill across the highway grew dusky and sharp. The towns and orchards in the valley to the south were dissolving into the blue light. Only the thin band of river held a spot of sun.

Now the sky to the west deepened to indigo, a color never seen. A dark sky usually loses color. This was saturated, deep indigo, up in the air.

With an awed and terrified eye to what Maria Mitchell called “the un-sunlike sun,” Dillard shudders at the incomprehensible strangeness of it all:

I turned back to the sun. It was going. The sun was going, and the world was wrong. The grasses were wrong; they were now platinum. Their every detail of stem, head, and blade shone lightless and artificially distinct as an art photographer’s platinum print. This color has never been seen on earth. The hues were metallic; their finish was matte. The hillside was a nineteenth-century tinted photograph from which the tints had faded. All the people you see in the photograph, distinct and detailed as their faces look, are now dead. The sky was navy blue. My hands were silver. All the distant hills’ grasses were fine-spun metal which the wind laid down. I was watching a faded color print of a movie filmed in the Middle Ages; I was standing in it, by some mistake. I was standing in a movie of hillside grasses filmed in the Middle Ages. I missed my own century, the people I knew, and the real light of day.

[…]

Gary was light-years away, gesturing inside a circle of darkness, down the wrong end of the telescope. He smiled as if he saw me; the stringy crinkles around his eyes moved. The sight of him, familiar and wrong, was something I was remembering from centuries hence, from the other side of death: Yes, that is the way he…

The post Into the Chute of Time: Annie Dillard on the Stunning Otherworldliness of a Total Solar Eclipse appeared first on FeedBox.