Author: Abbey Perreault / Source: Atlas Obscura

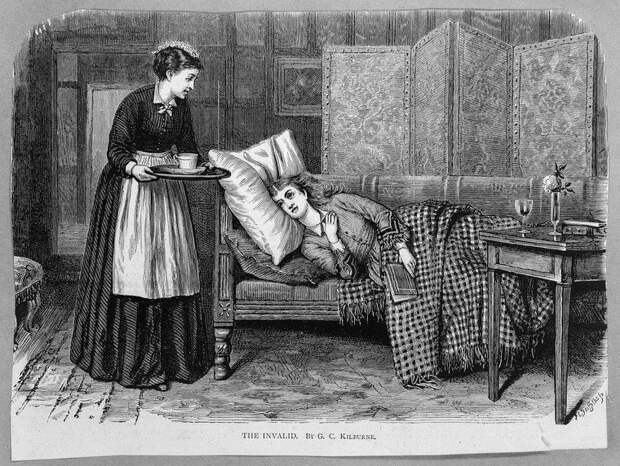

For over a month, “Mrs. C” laid in bed, gulping down quarts of milk. Aside from occasionally sitting up and relieving herself, the 33-year-old New Englander remained horizontal.

She had been deemed sick, or “wearied” at the least. But according to Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, his strict “rest cure” regimen had her on the mend. By the end of the month, she’d gained 40 pounds and a spot among his most successful cases.The rest cure that Mitchell pioneered rose to surprising popularity in the late 1800s, and several physicians adopted and practiced the treatment for decades. Only later did it become a textbook example of the disturbing nonlinearity of American medical progress, the quackery that can live alongside rigorous medical innovation.

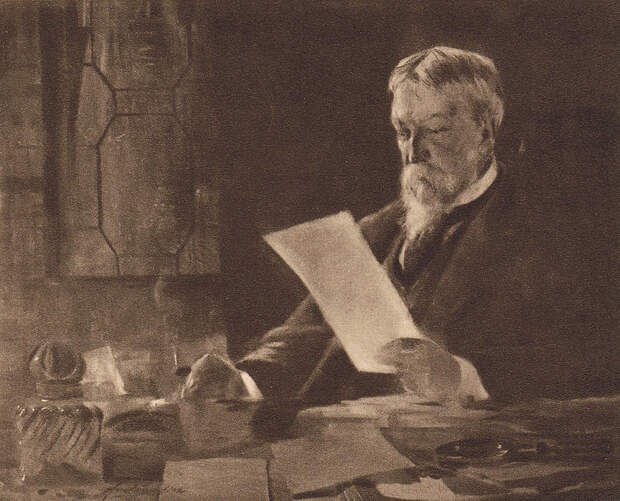

In the 19th century, the practice of psychiatry was rapidly evolving, and Mitchell, a neurologist from Pennsylvania, was at its forefront. The Civil War created a fresh need for young physicians willing to cut their teeth on the battlefield, particularly psychiatrists able to work with wartime trauma and surgeons treating injuries of the nervous system. New front-loading rifles and flattening bullets called “minnie balls” burst through bone and tore across tissue, leaving soldiers with devastating wounds treated by rapid amputation. Arms and legs were removed in mere minutes, and by the war’s end, tens of thousands of limbs had been amputated.

Mitchell found his place on the battlefield as a young surgeon, working at a specialty ward in Philadelphia.

He quickly took an interest in the not-yet-understood “nerve injuries” of amputees who experienced inexplicable, ghostly pain lingering where an arm or leg had once been. Mitchell wrote extensively on the subject, and coined the phenomenon “phantom limb syndrome.” As a quickly ascending physician in the fledgling field, he was awarded the title “Father of Modern American Neurology.”But Mitchell’s interest in “nerve injuries” began to branch beyond the battlefield. After the war, he became increasingly concerned with the neurological and biological effects of a technologically advancing America. “Have we lived too fast?” he asks in his 1871 book, Wear and Tear. The “cruel competition for the dollar,” he posits, along with the “racing speed which the telegraph and railway … introduced into commercial life” had planted something insidious in society, as well as within the human body.

American progress, he believed, was not without its neurological consequences. Something must be amiss among the urban elite, who were at the crux of rapid change and hurtling trains. Modernity, he posited, could deplete finite stores of “nervous energy,” leaving bodies and minds exhausted and sick. And when people overexert their minds, the only way to return to normalcy was to rest.

According to the neurologist, a person sick with “neurasthenia,” a term coined by a contemporary of Mitchell’s, might show symptoms ranging from headaches to lethargy, or weight loss to impotence. For men, the antidote was simple: Go West, chop some wood, maybe even cook some mannish meat over a rip-roaring fire. In a way, it was the 19th-century, professionally-prescribed analogue to a trip to the dude ranch.

But the cure was not quite so simple for women. Ladies, too, found themselves impaired by the pace of modern life, or, at least, swept up in the medical trend. More specifically, white, upper-class, educated women came to dominate Mitchell’s patient demographic. Women who occupied privileged positions like this, who were often writers and artists, had been increasingly afforded time outside of the home, the opportunity to socialize, and higher education. But using their minds so extensively, Mitchell believed, could easily deplete their energy and fry their fragile nerves.

Mitchell proceeded to prescribe the rest cure almost exclusively to these women—“nervous women,” writes Mitchell, “who, as a rule, are thin and lack blood.” And the way to quell the overexerted brain and depleted blood supply of a woman was to, essentially, prescribe her a long, milky, much-needed rest.

According to author and historian Dr. Jennifer Lambe, a number of symptoms brought women to Mitchell. Often, they looked like what…

The post The ‘Father of American Neurology’ Prescribed Women Months of Motionless Milk-Drinking appeared first on FeedBox.