Jennifer Zaspel can’t explain why she stuck her thumb in the vial with the moth. It was just some after-dark, out-in-the-woods zing of curiosity.

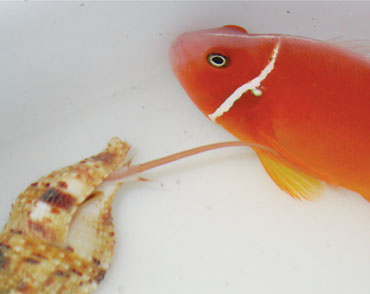

She had been catching moths in the Russian Far East. On this July night, she had just eased a Calyptra into a plastic collecting vial. Its brownish forewings looked like a dried leaf. Of the 17 or so largely tropical Calyptra species, eight were known vampires. Males tend to dine on fruit. But on occasion they will drive their hardened, fruit-piercing mouthparts into mammals and sip some fresh blood. They feed off animals such as cattle, tapirs and elephants — even humans.

Zaspel, however, thought she was outside the territory where she might find a vampire species. She had caught C. thalictri. This species ranges from Switzerland and France eastward into Japan. And it’s widely known as a strict fruitarian. (Fruitarian means something only eats fruit.)

Before capping the vial containing this moth, “I just for no good reason stuck my thumb in there to see what it would do,” Zaspel recalls. To her great surprise, “It pierced my thumb and started feeding on me.”

So make that eight-plus Calyptra vampires.

Zaspel is an entomologist now at the Milwaukee Public Museum in Wisconsin. And she still is puzzling over the genetics of the moths at the two Russian field sites she visited in 2006. Males there will bite a researcher’s thumb if offered. But genetic testing so far shows the moths are part of a vast, otherwise mild-mannered species.

Which is just as well. As vampires go, these moths are not stealth biters. “I would compare it to a bee sting,” Zaspel says. For the sake of moth science, one of Zaspel’s colleagues voluntarily tried, despite the pain, to see how long a moth would keep feeding if no one brushed it away. The bite lasted 20 minutes!

Such bites definitely will get noticed. For these moths and other real-life vampires, being smacked to a smear is a bigger danger than getting staked through the heart.

Nabbing the occasional red lunch, or managing to survive on nothing but blood, is far more difficult than it looks in the movies. Relatively few animals manage this lifestyle. And all are indeed remarkable. Vampires include some insects and other arthropods, a few mollusks, some fishes and birds on occasion. Oh, and of course, there are three types of bats.

When dining on blood, there are pressures to gorge as much as possible at each meal. Such heroic volumes, however, can be outright toxic. At the same time, a blood meal is not nutritionally well-rounded. Some key nutrients are missing. Surviving this way takes guts as well as other specialized traits.

Modern tools of genetics and molecular biology are revealing what hidden specializations are needed for blood feeding. Science also is helping to make sense of the lifestyles that go to different extremes — even mouth-to-mouth blood donation.

Many of these biological adaptations would never fit among the showy strengths of the immortals of Twilight or True Blood. But the abilities could certainly count as superpowers.

Big dinner

To grasp the risks true vampires take, imagine an animal 35 million times your weight. Now bite it hard enough to make it bleed.

And risk making it mad.

“You can easily get killed by the host,” observes Pedro L. Oliveira. This insect molecular physiologist works at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. The 35 million multiplier describes a 2-milligram (0.00007-ounce) female mosquito attacking a 70-kilogram (150-pound) human. These measurements came from an article Oliveira coauthored on nutritional overload in bloodsuckers. It appeared in the August issue of Trends in Parasitology.

Moreover, finding that giant blood source isn’t easy. “If you go into a forest, you have hundreds of meters separating one vertebrate host from another,” he notes. “Hundreds of meters would be several kilometers [a mile or two] for us.” Then the tiny vampire has to find a capillary — a tiny blood vessel — for biting that is just a few millimeters (about one-tenth of an inch) from the surface of the host’s skin. On a human victim, Oliveira estimates, only about 10 percent of the skin acreage will do.

With so many difficulties and dangers, “most of these guys try to minimize the number of visits,” Oliveira says. They drink fast, and they drink big. A young kissing bug, with its deceptively friendly nickname, can spread the debilitating and possibly fatal Chagas disease. That bug needs only minutes to down about 10 times its weight in blood.

To relate this to human physiology — forget it. There are people who intentionally drink blood (which is another story). But what they down is small in terms of what a real vampire would take away. It would be equivalent to the amount of swallowed blood from a long nosebleed, which can give a human diarrhea, notes Tomas Ganz. He’s a physician at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Fresh blood is difficult for the human gut to process. Plus, too little of the water in blood gets extracted and routed to the kidneys.

With such big blood meals, ingredients that would be harmless or healthful in small amounts now can prove toxic, Oliveira says.

Remove the water in blood. What’s left is almost 90 percent pure protein. Oliveira got an inkling of something perilous in that protein when his lab was exploring the genetics of one of the Americas’ kissing bugs.

This Rhodnius prolixus (ROD-nee-us Pro-LIX-us) has a rounded rear and body that narrows to a skinny little head. The bug lurks in crevices indoors or out. At night both males and females search for humans, their pets or other vertebrates pulsing with a good blood dinner. To be successful, this bug has evolved vampire superstealth. A kissing bug can bite a sleeper without waking that person. The bites of mosquitoes and ticks deliver pathogens in saliva. But a kissing bug delivers the Chagas disease parasite through its excrement. The bug leaves that gift on its host.

Researchers in 2014 detected many amino acids in that huge drink. The bugs had a massive array of special enzymes available to break down only one of them — tyrosine (TY-roh-seen) — as it washed into the kissing bug gut. Finding those tyrosine-busting enzymes in that gut is “kind of strange,” Oliveira says. In mammals, the liver and kidneys are the only organs with enzymes to break down tyrosine. Then again, most mammals don’t flood their guts with an overwhelming river of protein.

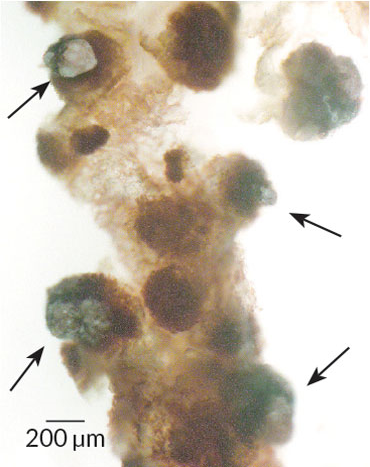

In the lab, researchers messed with the kissing bug to sabotage its breakdown of tyrosine. They either disabled genes or chemically blocked the enzymes. When changed in this way, the bugs died after dining. Oliveira and colleagues reported this last year in Current Biology.

Some of the dead bugs had crystals of tyrosine piercing right through the gut lining. This allowed their gut contents to leak into their body cavity. This discovery, the researchers now propose, might someday give molecular biologists their own drug to serve as a vampire-killing stake.

Blood feeding in insects and other arthropods has evolved multiple separate times (some say 21). But often the vampires have…

The post Sucking blood isn’t an easy life, even for vampires appeared first on FeedBox.