Author: Miss Cellania / Source: Neatorama

(Image credit: Stan Shebs)

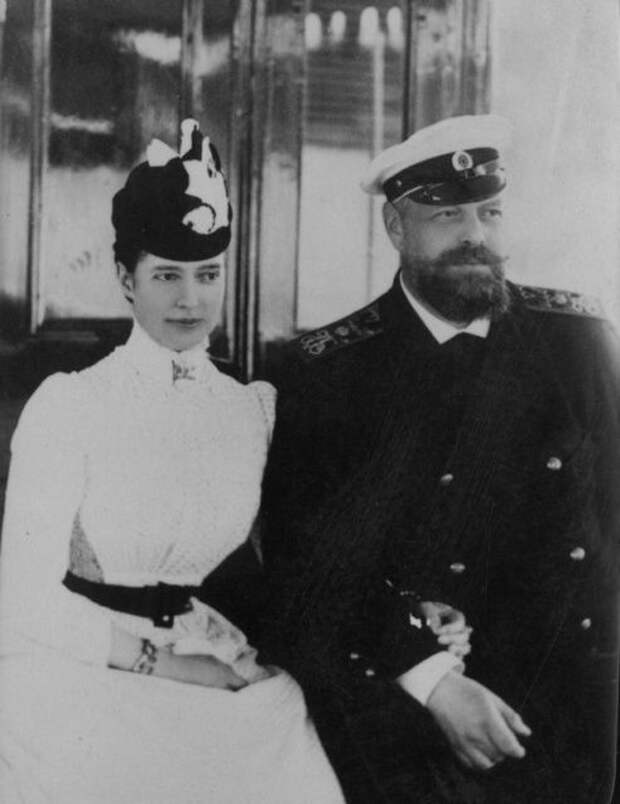

Unless you happen to be a Russian history buff, you probably don’t know much about Czar Alexander III. But if you’re a fan of Fabergé eggs, you have him (and Carl Fabergé, of course) to thank for them.

HOW EGGS-CITING

In 1885 the emperor, or czar, of Russia, Alexander III, placed an order with his jeweler for a decorative Easter egg for his wife, the czarina Marie Feodorovna.

Alexander had given his wife jeweled Easter eggs before: Easter was the most important holiday on the Russian Orthodox calendar, and eggs were traditionally given as gifts. But this year’s egg would be different, because Alexander placed his order with a new jeweler: 38-year-old Carl Fabergé.Fabergé differed from other jewelers who served the Imperial court in that he was more interested in clever design and exquisite craftsmanship than in merely festooning his creations with gold and precious gems (though his eggs would have plenty of those) without showing much imagination. “Expensive things interest me little if the value is merely in so many diamonds and pearls,” he said.

NEST EGG

That first Imperial Easter egg was very plain indeed, but only on the surface: known today simply as the 1885 Hen Egg, it was 2½ inches long and made of gold but had a plain white enamel shell to give it the appearance of an ordinary duck egg. When the two halves of the egg were pulled apart, they revealed a golden yolk that in turn opened to reveal a golden hen “surprise” sitting on a nest of golden straw. The hen was hinged at its tail feathers and split open to reveal a small golden replica of the Imperial crown; hanging from the crown was a tiny ruby pendant that Marie Feodorovna could wear around her neck on a gold chain that came with the egg.

(Image credit: )

Marie Feodorovna loved the egg, and for the rest of his life, Czar Alexander bought all of her Easter eggs from Fabergé. Alexander gave the jeweler great latitude in designing the eggs and set only three requirements: 1) the eggs had to be egg-shaped; 2) they had to contain a surprise; and 3) Fabergé’s designs could not repeat themselves. Those three requirements aside, Fabergé was free to do whatever he wanted. The jeweler made a point of not revealing anything to Alexander about each egg until he delivered it a few days before Easter so that the czar could enjoy the suspense as well. “Your Majesty will be content,” was all he’d say.

BY THE DOZEN

Not much is known about the second egg, Hen with Sapphire Pendant, which Fabergé made for 1886; it disappeared in 1922. For his third egg, in 1887 Fabergé made a golden egg not much larger than a hen’s egg. It sat on a gold pedestal with three lion’s paw feet. Pressing a diamond on the front of the egg caused its lid to pop open, revealing a ladies’ watch face inside. The watch was mounted on a hinge and could be tilted upright, allowing the egg to be used as a clock.

In the years that followed, the eggs produced in Fabergé’s workshop became larger and more elaborate as teams of craftsmen worked the entire year, sometimes longer, to complete the eggs. The Danish Palaces Egg for 1890 contained a folding screen comprising 10 miniature paintings of the palaces and royal yachts that Marie Feodorovna, a Danish princess, remembered from her childhood. The 1891 Memory of Azov Egg contained a gold and platinum model of an Imperial Navy ship of the same name, which had taken the future czar Nicholas II and his brother George on a tour of the Far East in 1890. The egg was carved from solid bloodstone (green quartz speckled with red), and the model inside was an exact replica of the Memory of Azov and floated on a blue sea of aquamarine. The ship was accurate down to its diamond portholes, movable deck guns, and tiny gold anchor chain.

TWO OF A KIND

If Fabergé feared losing his best customer when Alexander III died in 1894 at the age of 49, he needn’t have worried. When Alexander’s son Nicholas II came to the throne in November 1894, he doubled the order to two eggs each year: one for his mother, Marie Feodorovna, and one for his wife, the czarina Alexandra. He bought them every year except 1904 and 1905, when the purchases were suspended during the Russo-Japanese War.

(Image credit: diaper)

Nicholas didn’t let the outbreak of World War I in 1914 stop him from buying Easter eggs, though the wartime eggs were more modest and subdued in…

The post The World’s Most Expensive Eggs appeared first on FeedBox.