Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

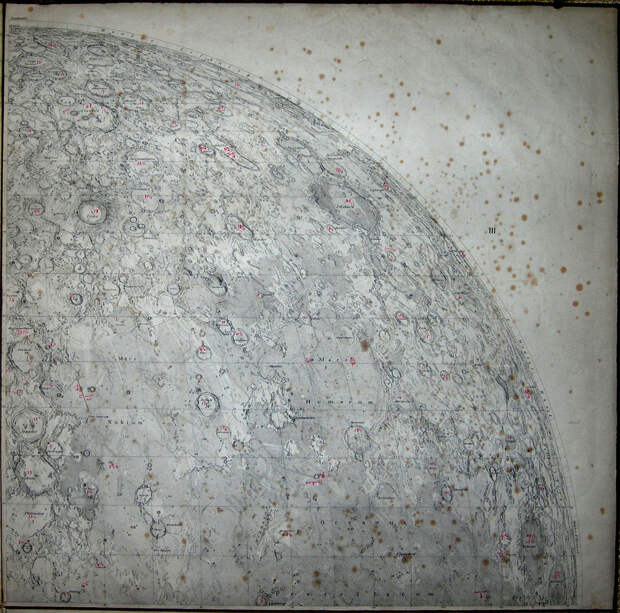

As lunar craters go, it is a small one—a ding from some long-ago collision. At 3,000 feet deep and roughly three miles across, it sits on the Sinus Medii, from the Latin for “Central Bay,” a holdover from when early astronomers mistook the Moon’s dark volcanic plains for bodies of water.

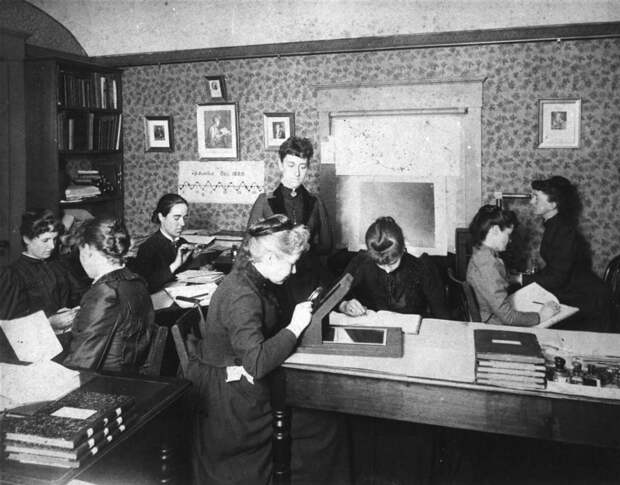

The crater itself is named Blagg, after amateur astronomer Mary Blagg. Though her work is largely forgotten today, Blagg was a pioneer in the ever-expanding field of naming every little thing in the solar system.Women have worked in astronomy for centuries, often without recognition, as observers, number-crunchers, and innovators. In the 19th century, American Maria Mitchell studied sunspots, discovered a comet, and was appointed professor of astronomy at Vassar College. Around the same time, Williamina Fleming waxed poetic about female astronomers at the 1893 World’s Fair and recruited roughly 20 female assistants to help her analyze photographs of stars at the Harvard College Observatory. More recently, Nancy Grace Roman, NASA’s first chief of astronomy, was dubbed the “Mother of Hubble” for her role in helping create the groundbreaking space telescope. It is hard enough for women in the male-dominated field to gain recognition for their contributions, and even harder for people like Blagg, in a support field such as planetary naming.

“I don’t think anybody is really going to get famous being involved in nomenclature,” says Tenille Gaither, a geologist at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the assistant database manager for the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, which is today the final word on the names and coordinates of all sorts of features, from mountains and plateaus to valleys and dark spots, in our solar neighborhood. “It’s not a field in which people get renown for any kind of discoveries.

”Gaither is a current steward of a particular tradition. From the 1880s to the present, women have helped define, describe, and organize the our solar system, from long-visible features on Mars to topographical features that have only recently come into view on a Jovian satellite.

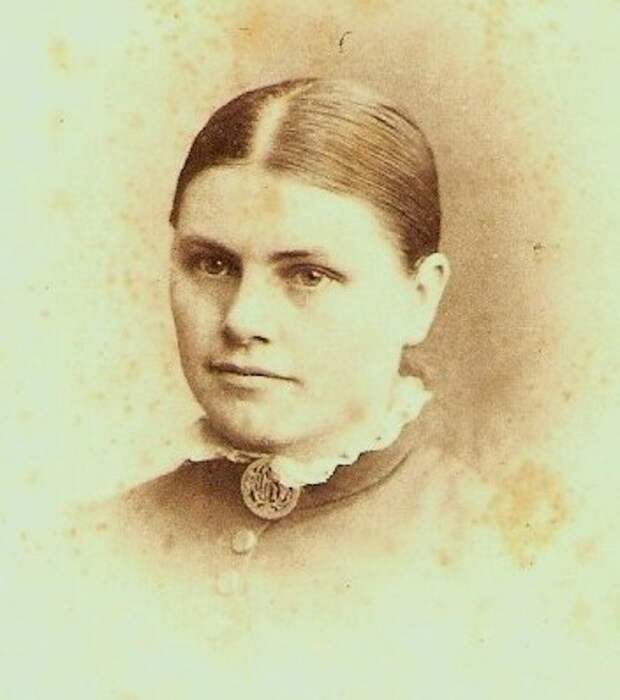

Mary Adela Blagg was born in 1858 in the English town of Cheadle, near Staffordshire. The daughter of a lawyer, her formal education ended after boarding school in London, where she studied German and algebra. When her mother died in 1896, Blagg took over the household and management of the family estate, Greenhill.

She rarely ventured far from home, but Blagg’s mind wandered. She was good at chess, and she enjoyed solving the puzzles printed in the weekend paper. She poured over her brothers’ schoolbooks to nurture her interest in math. She also threw herself into charity work, such as tending to refugee children evacuated from Belgium during World War I.

Blagg didn’t arrive at astronomy until she was nearly 50, when she attended a lecture by astronomer J.A. Hardcastle. He was working with mathematician and stargazer Samuel Arthur Saunder to deduce the positions of lunar craters from a series of photographs captured in Paris. The researchers had grown frustrated, in part because the craters they were interested in—and other features on the Moon’s surface—went by a slew of different names.

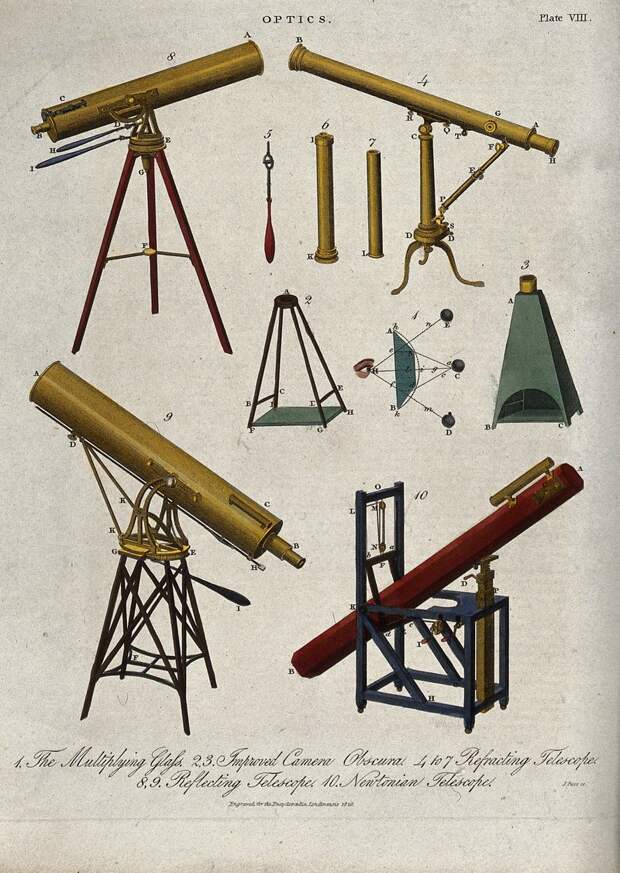

The solar system is vast, and the universe that provides its backdrop in the sky much more so. People have long named stars and constellations and tracked the movements of the planets, but if they wanted to look at anything in greater detail, there was, for much of human history, just one obvious target—the Moon.

Selenography—the study of the surface of the Moon—boomed around the early 1600s, when people first started seeing our natural satellite through telescopes and describing what they saw. Before powerful telescopes and spacecraft (and, eventually, visits) brought us close views, most early selenographers made their own maps, and chose their own names for the features they observed. A particular crater, for example, might have three names, and this was no help at all if one wanted to compare observations. So, in 1905, Saunder pitched the British astronomy community on a novel concept: standardization.

As the researchers set out on the task, they thought of Blagg. She had stayed in touch after the lecture, and demonstrated herself to be meticulous and indefatigable. (She had, for instance, compiled more than 4,000 observations of scintillating stars she could see from her hometown.) Saunder asked if she would help coax the chaos into order. She happily joined the effort.

The Committee on Lunar Nomenclature first…

The post Who Keeps Track of All the Craters on the Moon? appeared first on FeedBox.