Author: Laurel Hamers / Source: Science News

Techniques that put natural evolution on fast-forward to build new proteins in the lab have earned three scientists this year’s Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Frances Arnold of Caltech won for her method of creating customized enzymes for biofuels, environmentally friendly detergents and other products. She becomes the fifth woman to win the Nobel Prize in chemistry since it was first awarded in 1901. Gregory Winter of the University of Cambridge and George Smith of the University of Missouri in Columbia were recognized for their development and use of a technique called phage display. This molecule-manufacturing process can generate biomolecules for new drugs.

The trio will share the 9-million-Swedish-kronor prize (about $1 million), with Arnold getting half and Winter and Smith splitting the other half.

“Wow, well-deserved!” says Paul Dalby, a biochemical engineer at University College London. “Protein engineering as a field is absolutely founded upon their work.”

In the 1990s, Arnold wanted to make an enzyme that would break down a milk protein called casein in an organic liquid, rather than in water. Instead of trying to manually sculpt the chemical building blocks of that enzyme, subtilisin E, to give it the right properties, she opted for a more hands-off approach.

ENZYME EVOLUTION

Arnold’s insight “was to recognize that the most amazing molecules in the world weren’t created by chemists, but rather by the biological world,” says Jesse Bloom, a microbiologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. “Biology didn’t make these chemicals using the methods we might learn in an organic chemistry class — rather, it worked by evolution.”

Arnold first made many copies of the original enzyme, each with a different set of genetic mutations. She then inserted the genes for those enzymes into bacteria. These bacteria served as living factories, churning out many copies of each enzyme variant. Arnold picked out the version that did the best job breaking down casein in an organic solvent and repeated the mutation process, starting with that enzyme.

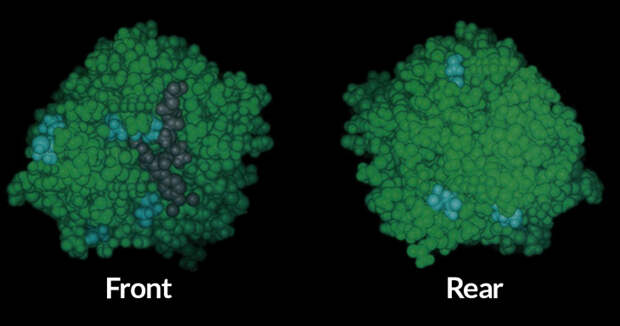

Frances Arnold’s lab put the enzyme subtilisin E through directed evolution to make it more active in an organic liquid. The changes to create the first variant are shown here in yellow; the molecule was then further evolved to include the additional mutations shown in blue. Molecules and…

The post Speeding up evolution to create useful proteins wins the chemistry Nobel appeared first on FeedBox.