Author: Eric J. Wallace / Source: Atlas Obscura

Forty-two years ago, Gabriele Rausse received a phone call from a childhood friend who told him he had to “drop everything and come to America.”

The phone call was from one viticulturist to another.

Rausse was 30 years old and working on a French vineyard. (He had been working in Australian wine, but his visa was revoked on a technicality.) His childhood friend, Gianni Zonin, was president of the Italian winemaking company Casa Vinicola Zonin. The two had grown up together in Italy’s Veneto wine region, and their phone call forever changed the U.S. wine industry.Together, Zonin insisted, he and Rausse were going to establish the first Virginia vineyard to have commercial success growing Vitis vinifera, the species of grape responsible for fine wine.

“I was worried,” says Rausse. “All I could think was, ‘My God, he’s gone insane.’”

The year was 1976, and at that time, the idea of making premium wine in Virginia was crazy. While Napa Valley was establishing itself as a world-class producer, few had taken the idea of making European-style fine wine on the East Coast seriously since Thomas Jefferson tried and failed some 200 years earlier. The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services warned that vinifera varieties would not survive the winter. Even if they did, native pests and diseases would kill them off. According to wine-historian and journalist Richard G. Leahy, East Coast vineyards of the time made beverages that were almost universally “more relatable to winos than wine.” Crafted from French-American hybrids or native grapes that yielded flavors comparable to bubble-gum (think Boone’s Farm), the wines were essentially considered a bad-joke by connoisseurs.

On the call, Rausse debated how to tactfully turn down his friend. But he had a second thought.

“My only plan was to get my visa fixed and return to Australia. Suddenly, I realized going to America would let me practice my English,” he says. “So, I accepted. But with a big caveat. I told Gianni, ‘I’ll help you with your fool’s errand. But once I get my visa, I’m gone.’”

Zonin had considered establishing an American vineyard since visiting Napa Valley in 1961. He hoped to create a distribution center and further Casa Vinicola Zonin’s reach. He also worried that his family’s 11 vineyards might be nationalized by communists who seemed capable of winning elections in Italy. After inheriting the company presidency, the sixth-generation scion set out on a grueling survey of “every American viticultural region willing to build a winery.” After traveling to Oregon, New York, and California, he visited an Italian-born friend at the University of Virginia.

The visit coincided with the bicentennial of Jefferson breaking ground at his Monticello estate. Charlottesville was celebrating.

“I remember studying Jefferson’s attempts to cultivate vinifera in Virginia,” says Zonin. “I was fascinated by the idea of a president being a viticultural pioneer.”

Touring Monticello and the mountainous countryside surrounding Charlottesville, Zonin was reminded of his home in northern Italy. “It was so beautiful and somehow familiar. I was falling in love with the area,” he muses. He began to ask questions about soil, rainfall, and climate.

Then he learned of Jefferson’s enlistment of one of the 18th century’s most prestigious wine personalities, Philip Mazzei, an Italian, to manage his experimental vineyard. He also learned of Jefferson’s assertions that the venture would have succeeded if Mazzei’s vines had not been trampled by horses during the American Revolution. Says Zonin, “I began to think, ‘Maybe they chose this place for a reason.’”

Zonin returned to Italy, but Charlottesville stayed on his mind. In his spare time, he studied the region’s microclimate and traced the city’s latitude across the globe, comparing the data to that of sister regions in Italy.

“I noticed the average rainfall and temperature were nearly identical to areas in central Italy,” says Zonin. Virginia had long summers and mild, extended falls that often featured low rainfalls—ideal conditions for growing grapes. “That’s when I knew I wasn’t going to establish just another California vineyard. I was going to do this in Virginia.”

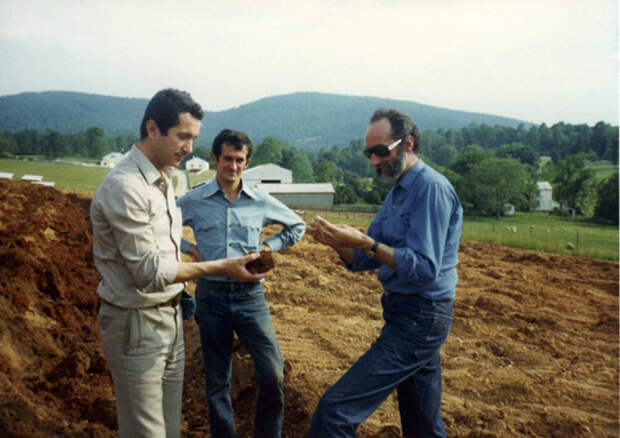

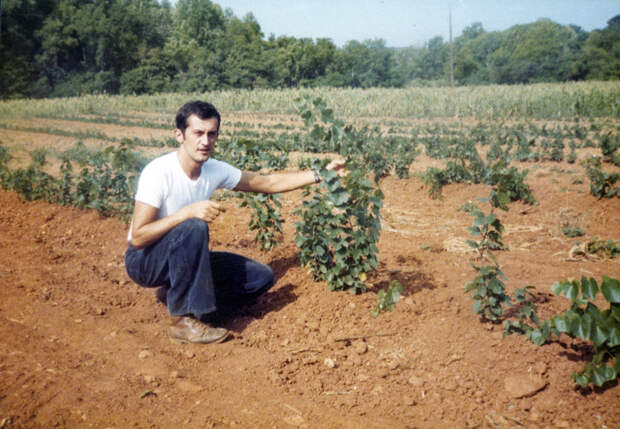

Rausse’s plane touched down in Charlottesville in early 1976. To his chagrin, he discovered Zonin had yet to buy a property. Over the next few weeks, they toured some 25 estates.

“They all looked very good. But Gianni kept saying: ‘No, this is not right,’” explains Rausse.

Then came Barboursville. The hilly, 900-acre estate dated to the 18th century and featured the ruins of an 1814 manor designed by Jefferson for his friend and political ally, James Barbour. Zonin took this history as a sign. Or, as Rausse puts it, “like we were being smiled upon by Mr. Jefferson.”

Though the purchase came as a relief, Rausse soon grasped the contentiousness of their project. “Everyone who knew anything about making wine was laughing at us, and doing it very publicly,” he says. “They didn’t just say, ‘Oh, this is silly.’ I believe they hoped for us to fail.”

Op-eds criticized them as buffoons. Locals cracked jokes about them being in the Mafia. An arsonist burned down the barn housing their winery. Farmers who had planted French-hybrid vines spoke out against them. Officials viewed them with suspicion—as if the endeavor were actually a ruse to undermine the East Coast’s so-called wine industry or mislead local farmers.

When Virginia’s commissioner of agriculture ascertained what was happening, he summonsed Rausse to a conference room in Richmond. For two hours, 24 scientists and professors took turns lecturing. Plant pathologists explained American diseases and virologists told of native viruses. One after another, they said Rausse would fail. The meeting adjourned…

The post How Two Italians Achieved a 200-Year-Old Dream of Virginian Wine appeared first on FeedBox.