Author: Anne Ewbank / Source: Atlas Obscura

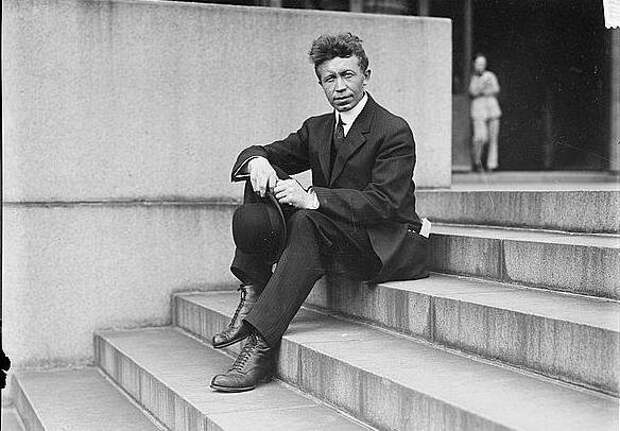

In 1928, Vilhjalmur Stefansson was already world-famous. A Canadian anthropologist and consummate showman, he promoted the idea of a “Friendly Arctic,” open to exploration and commercialization.

Newspapers and magazines breathlessly covered his sometimes-deadly escapades in the Arctic, including his discoveries of some of the world’s last unknown landmasses, and, more controversially, a group of “blond” Inuinnait who he claimed partially descended from Norse settlers. But for a little while, another facet of Stefansson’s life drew media attention. While living in New York for a year, Stefansson ate nothing but meat.Today, this would be known as a ketogenic, or a no-carb diet. It’s in vogue as a weight-loss tactic: The idea is that limiting carbohydrates, which are an easy source of energy, can make the body burn fat.

But Stefansson wasn’t trying to burn fat. Instead, he wanted to prove the viability of the Inuit’s meat-heavy diet. In the Arctic, people mainly ate fish and meat from seals, whale, caribou, and waterfowl, while brief summers offered limited vegetation, such as cloudberries and fireweed. Meals could be frozen fish, or elaborate treats such as the creamy fat-and-berry dish akutaq. Western doctors thought it was a terrible way to eat.

Even in the 1920s, a diet light on meat and heavy on vegetables was considered optimal. Vegetarians were more numerous than ever, and raw vegetables, particularly celery, took on a virtuous shine. This was the era of John Harvey Kellogg, famed for not only cereal, but his health resort in Battle Creek, where no meat was on the menu. (Stefansson was even a guest there, perhaps briefly swapping steak for snowflake toast.)

It’s now widely acknowledged that the Inuit subsistence diet is quite balanced. As biochemist and Arctic nutrition expert Harold Draper told Discover magazine, there are no essential foods, only essential nutrients. Vitamin A and D, so easily available from milk, vegetables, and sunlight, can also be obtained from oils within sea mammals (particularly livers) and fish. And fresh meats and fish, prepared raw, contain trace amounts of vitamin C, a fact that Stefansson was the first Westerner to realize. It only takes a little to prevent scurvy.

During Stefansson’s day, though, doctors, dietitians, and general opinion considered the meat-heavy diets of the Arctic peoples poor and improbable. Stefansson’s year of eating carnivorously was a high-profile attempt to prove them wrong.

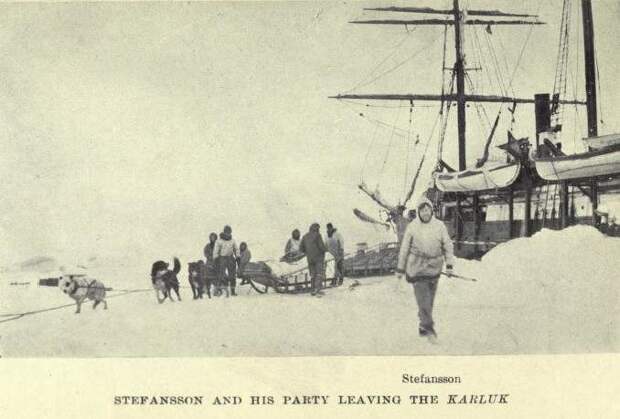

Stefansson himself had only come around to the diet after an extended stay in the Mackenzie Delta of the western Arctic in 1906. When a ship carrying his supplies failed to materialize, he instead depended on the hospitality of a local family. At first, he roamed far and wide to build up an appetite for the plain roasted fish he received. “When I got home I would nibble at it and write in my diary what a terrible time I was having,” he wryly wrote later. But he gradually learned to enjoy the alternatively boiled, frozen, and fermented fish that he watched Inuvialuit women prepare.

It was during this first extended stay that he started to object to what he had been told about the Arctic diet, especially his peers’ horror over the “uncivilized” practice of eating fermented fish. “I tried the rotten fish one day, and if memory servers, liked it better than my first taste of Camembert,” he wrote. It wasn’t hard to notice that the…

The post The Arctic Explorer Who Pushed an All-Meat Diet appeared first on FeedBox.