Author: Elliot Williams / Source: Hackaday

This year’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) triennial review (PDF, legalese) contained some great news. Particularly, breaking encryption in a product in order to repair it has been deemed legal, and a previous exemption for reverse engineering 3D printer firmware to use the filament of your choice has been broadened.

The infosec community got some clarification on penetration testing, and video game librarians and archivists came away with a big win on server software for online games.Moreover, the process to renew a previous exemption has been streamlined — one used to be required to reapply from scratch every three years and now an exemption will stand unless circumstances have changed significantly. These changes, along with recent rulings by the Supreme Court are signs that some of the worst excesses of the DMCA’s anti-circumvention clause are being walked back, twenty years after being enacted. We have to applaud these developments.

However, the new right to repair clause seems to be restricted to restoring the device in question to its original specifications; if you’d like to hack a new feature into something that you own, you’re still out of luck. And while this review was generally favorable of opening up technology to enable fair use, they didn’t approve Bunnie Huang’s petition to allow decryption of the encryption method used over HDMI cables, so building your own HDMI devices that display encrypted streams is still out. And the changes to the 3D printer filament exemption is a reminder of the patchwork nature of this whole affair: it still only applies to 3D printer filament and not other devices that attempt to enforce the use of proprietary feedstock.

Wait, what?Finally, the Library of Congress only has authority to decide which acts of reverse engineering constitute defeating anti-circumvention measures. This review does not address the tools and information necessary to do so. “Manufacture and provision of — or trafficking in — products and services designed for the purposes of circumvention…” are covered elsewhere in the code. So while you are now allowed decrypt your John Deere software to fix your tractor, it’s not yet clear that designing and selling an ECU-unlocking tool, or even e-mailing someone the decryption key, is legal.

Could we hope for more? Sure! But making laws in a country as large as the US is a balancing act among many different interests, and the Library of Congress’s ruling is laudably clear about how they reached their decisions. The ruling itself is worth a read if you want to dive in, but be prepared to be overwhelmed in apparent minutiae. Or save yourself a little time and read on — we’ve got the highlights from a hacker’s perspective.

Right to Repair, But Not to Tinker

Support of the right to repair is the big win coming out of this week’s ruling, and strangely enough the legality of hacking on the firmware of children’s toys stems from the original work of farmers to fix their tractors. All land vehicles got an exemption in 2015 (PDF) that included decrypting the ECU and engine diagnostics, “undertaken by the authorized owner” and excluding the entertainment and telematics subsystems. It was argued that the exemption for the entertainment system was intended to prevent people from turning their cars into mobile copyright violation machines.

But based on strong lobbying by repair-industry groups and by farmers who wanted to fix the air conditioning in their tractors, these restrictions were lifted this year. Not only can you work on any system necessary, but you can authorize others to do so on your behalf. And the class of use cases, “Class 7: Computer Programs — Repair”, has been expanded to include “other types of software-enabled devices, including appliances, computers, toys, and other Internet of Things devices”. This is a big deal for anyone who wants to fix anything with firmware.

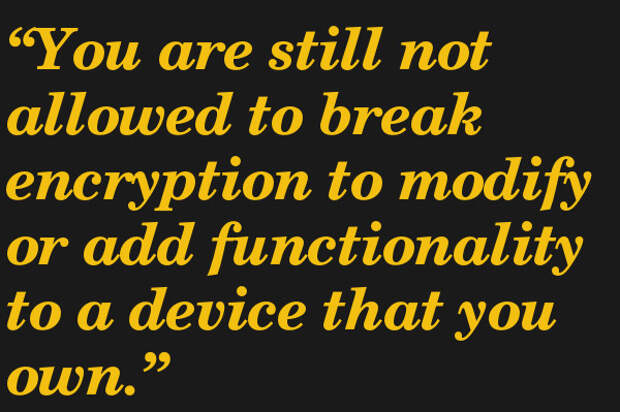

But it is not a victory for hackers, tinkerers, or anyone who wants to do something original with a device that they own. In particular, the phrase “lawful modification” was included in a proposed draft of the ruling, along with a clause to allow “the acquisition, use, and dissemination of circumvention tools in furtherance of diagnosis, repair, and modification”. As mentioned above, circumvention tools are outside of the Library’s jurisdiction, so no ruling on tooling. And while the “lawful modification” clause was retained in the particular section covering vehicles, it was struck from the devices and IoT section with the rationale that it was “not defined with sufficient precision to conclude as a general…

The post DMCA Review: Big Win for Right to Repair, Zero for Right to Tinker appeared first on FeedBox.