Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“Resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied,” Zadie Smith counseled in the tenth of her ten rules of writing — a tenet that applies with equally devastating precision to every realm of creative endeavor, be it poetry or mathematics.

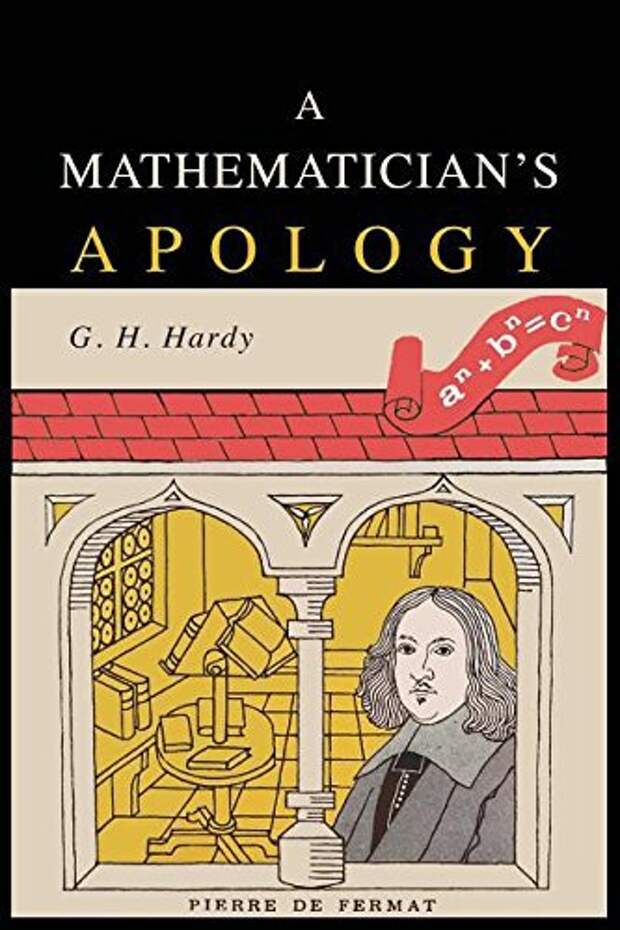

Bertrand Russell addressed this Faustian bargain of ambition in his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech about the four desires motivating all human behavior: “Man differs from other animals in one very important respect, and that is that he has some desires which are, so to speak, infinite, which can never be fully gratified, and which would keep him restless even in Paradise. The boa constrictor, when he has had an adequate meal, goes to sleep, and does not wake until he needs another meal. Human beings, for the most part, are not like this.”Ten years earlier, the English mathematician and number theory pioneer G.H. Hardy (February 7, 1877–December 1, 1947) — an admirer of Russell’s — examined the nature of this elemental human restlessness in his altogether fascinating 1940 book-length essay A Mathematician’s Apology (public library).

In considering the value of mathematics as a field of study and “the proper justification of a mathematician’s life,” Hardy offers a broader meditation on how we find our sense of purpose and arrive at our vocation. Addressing “readers who are full, or have in the past been full, of a proper spirit of ambition,” Hardy writes in an era when every woman was colloquially “man”:

A man who is always asking “Is what I do worth while?” and “Am I the right person to do it?” will always be ineffective himself and a discouragement to others. He must shut his eyes a little and think a little more of his subject and himself than they deserve. This is not too difficult: it is harder not to make his subject and himself ridiculous by shutting his eyes too tightly.

[…]

A man who sets out to justify his existence and his activities has to distinguish two different questions. The first is whether the work which he does is worth doing; and the second is why he does it, whatever its value may be. The first question is often very difficult, and the answer very discouraging, but most people will find the second easy enough even then. Their answers, if they are honest, will usually take one or other of two forms; and the second form is a merely a humbler variation of the first, which is the only answer we need consider seriously.

Most people, Hardy argues, answer the first question by pointing to a natural aptitude that led them to a vocation predicated on that…

The post Pioneering Mathematician G.H. Hardy on the Noblest Existential Ambition and How We Find Our Purpose appeared first on FeedBox.